- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

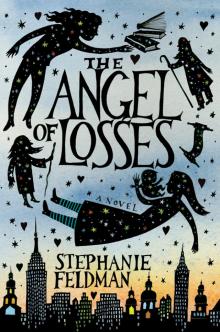

The Angel of Losses Page 22

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 22

I shuddered, and Grandpa’s hand closed over my shoulder. “I want my girls to live long, beautiful lives. I thought I could help you. You wouldn’t know loss.” He let go of me, and I sat back, giving him room to stand. “But you can’t stop loss. It’s the other side of life. It’s what the world is built on. And that’s all I wanted for us: to be of this world.”

Grandpa walked to the door and took the boy’s hand. The darkness fell away. Beyond them, a marble-tiled hallway gleamed. Grandpa looked at me one last time, then let Josef lead him away. I watched his shadow stretch across the floor and slide away as he took it with him toward whatever room in the celestial academy would now be his. I turned away, stepping into the hallway and shutting the door. I leaned my forehead against it and watched as the light spilling onto the hallway floor dimmed and finally went out. He was gone.

Downstairs, there was a knock at the front door.

I came to the bottom of the staircase. A dark shape moved in the frosted windows bordering the front door. Another knock. I could head to the back door—I could run across the lawn—I could jump the fence, circle the block. But instead I backed into the living room and stood rooted while the door shuddered and the knob finally turned.

A figure was silhouetted in the doorway. He moved into the front hall, slowly, hesitantly. The old man who had given me the amulet for Holly, named the babies in the hospital, watched over Grandpa’s body and stood with me at his funeral, the man who had found infinite shelves for books in a tiny Lithuanian basement, who had sealed the basement, his tunnel to the Holy Land, but only seemed to have disappeared.

He stepped into the living room. Even the whites of his eyes were blue now, the color of ice on a windshield. I felt dizzy, as if I had been unexpectedly blinded by bright light or overpowered by an awful scent. “Sit,” he said. “And we’ll talk.”

I fell back into the armchair, and he took the chair across from me.

“You said you’d rather it be me,” I said. “Okay. It can be me.”

“Eli warned you,” he said. He almost sounded concerned.

“I want my nephew to live.”

“What we do for the ones we love.” He paused. “The Angel of Losses will come to you soon. He will flatter you. He will tempt you to journey to the River of Stones, where you will meet a terrible end.”

“Well, I don’t believe in any of that stuff,” I said. “So I doubt he can persuade me.”

He laughed, a deep rasping laugh, and clapped his hands once. “Oh, the world I’ve lived to see. He’s not as stupid as you think. He will not talk to you about God.” The old man patted his left shoulder, where the magic letter burned, and with the faint smile still on his lips the gesture seemed nearly affectionate. I understood his meaning: It was the Sabbath Light I had to fear, and its own internal urge to return to its source; its estrangement from the angel so wrenching that it simultaneously destroyed and preserved its keeper. Yode’a suffered from a love that could not be suppressed or answered but that nevertheless drove him onward, and it had made a ghost out of him.

“Where is my sister’s husband?”

“Lying in the dirt. Talking to himself. The fool.”

“Stop,” I said, my anger flaming. “He’s just trying to save his son. That doesn’t make him a fool.”

“He’s a fool,” the White Rebbe repeated. “So are you. Foolish. Proud. Fierce. Like all of us. And through some error that earns us the only bit of Himself that God left behind before our exile.”

“No more talk,” I said.

He took a deep breath, pressed into the armrests, and slowly lifted himself onto his feet. He moved toward the kitchen, his steps deliberate, his posture slightly hunched, his gait slightly shaky. He had never appeared so elderly as he did now, snapping on the stark kitchen light and standing amid all the devices of modern life, the coffeemaker and the microwave, the magnetic knife rack gleaming above the stove.

Maybe he wanted something to drink or eat. Absurdly, I thought I should tell him which plates to use, which were meat and which were dairy, but before I could speak, he took a butcher’s knife from the rack and slashed his left arm above the elbow. The White Rebbe turned to me. A dark stain spread across his coat.

“Now,” he said. “Before it heals.”

I heard Grandpa’s plea again: Don’t trust him. Don’t do what he asks. But this time the words didn’t reverberate through my dreams or hiss through a haunted intercom. They were voiceless, just a memory. I turned my back to the White Rebbe. For an instant I wondered if this exchange might be my final, cosmic play against Nathan; the ultimate show of possessiveness over Holly and Eli. But no; for the first time in years, I felt like I had nothing to prove. This was bigger than me. “Close your eyes,” the old man asked, his voice low, reverent. “Do you see it?”

I closed my eyes and found myself in a vast, unpeopled landscape, walking beneath a bleached sky. With each step, rusty sand blew away, uncovering another gleaming angle, another silver joint, the skeleton of the world revealing itself to me, as a wordless roar urged me to walk on, walk on toward the infinite horizon.

“Yes,” I said. “I see it.”

“Will you carry it?”

“Yes.”

My shirt stretched and then there was a cold touch, the knife point against my middle rib, and then a pinch, and then a burn spread like a stain in cloth as my flesh parted.

I felt warmth skipping across my skin, the rippling corona of a star.

And cold spreading beneath it, ore threading stone.

And my veins prickling, the intricate weaving of my capillaries.

And my breath blooming like a flower, constricting like a pupil trained at the sun.

And my bones locking, hard and white as the moon.

And my nerves humming, a thousand compass needles spinning.

And my being circling, like the rings of a tree, from my core to the limits of my body, and then beyond my sense of—

THE KNIFE CLATTERED AGAINST THE FLOOR. THE EDGE SHONE dark with blood, and there were three drops of blood on the tile, perfectly round and a thousand feet deep, wells that trapped the scribes of history and the rumbling of eternal trains.

“What is going to happen to me?” I asked.

I didn’t want to be like Solomon—circling like a prehistoric shark through the dreams of a hundred lifetimes, his destination vague but insistent, his heart stowed away in a tarnished box. I didn’t want to be like my grandfather, not how he was at the end, bitter and mean and alone.

I didn’t want to be angry anymore.

“Eli wouldn’t be told what to do, and I doubt you will either, even if your instructor is an angel.” His coat sleeve was black with blood, dripped onto the floor in a rhythmic tapping.

The old man held up one finger in warning. “But don’t get cocky.” I sighed, and he reached out and held my hand. “You’re a good sister,” he said, comforting me as his tremors reverberated in my skin. “You’ll give your sister her family back. You have a strong will. Just don’t forget who you are. Whatever you lose, whatever you must let fall away from you.” He tapped his temple. “Keep that.”

I watched him walk carefully back across the living room, his steps uneven, a brand-new limp. The shadows swallowed him as he opened the front door.

“Holly won’t even know,” I called after him.

He stopped. His shoulders moved with his breath. Slow. Deep. “No,” he said. “But you will. Isn’t that enough?” And then the old man called forth the strength for another step, and then another, and he was gone.

THE CLOSED CEMETERY WAS UNLIT. I HAD BROUGHT A FLASH LIGHT, BUT I was reluctant to use it. What if there were guards, night watchmen? Was this trespassing? How could I explain myself? If I was caught here, in the middle of this story, before I could bring it full circle, I would be lost. I wouldn’t be able to pick up the thread again. I cupped one hand over the lens of the flashlight and thumbed the switch, sending the light through my fingers, highli

ghting streaks of green grass and white stones, fragments of engraving flashing black, as I tried to orient myself.

I listened for the penitent’s lament. “Arise,” I said under my breath, and something did—a wordless sobbing over the hill, and I followed it to my grandfather’s grave, which was strewn with charms and papers and an open book, brown pages flapping in the breeze. And there, amidst it all, was Nathan. My brother-in-law crouched, hunched over, his forehead in the grass. He rose from the ground, his face streaked with tears and dirt and, yes, blood, his beard glistening and his jacket open, his shirt torn, multiple necklaces hanging against his chest, his sleeves pushed above his elbows, a knife in hand. I recognized it. It was the blade that had sawed and smoothed a thousand leather boxes for a thousand miniature scrolls.

“I tried everything. Poultices. Amulets. Prayers. Eli has a secret name—even that didn’t protect him. I have no choice,” Nathan said. “You know who the man in the stories is. You know what he can do,” he said, accusing, his voice ragged.

I said nothing. The blade had absorbed my voice.

His left forearm was slashed with angry red lines that didn’t quite coalesce into a flame or a spiral or a hand. Blood flowed from his elbow to his wrist, from his palm to the knife, from the metal to the earth. “I can’t write it,” he confessed, his voice hoarse. “I see it on the page. I see where the lines should go. Here.” He dipped the knifepoint toward his arm, and I flinched. Could he sever an artery, bleed to death before me? “To here.” He moved it through the air. “But when I do it. It’s wrong.”

“Only one person can know it,” I said.

The lens through which I had once seen the world had slipped, and what I saw now was at once extraordinarily old and entirely new, lines sharper and distances longer, colors brighter and shadows layered. I had to learn to focus again. I was standing in the bitter night, in a graveyard, alone but for a sad man huddled on the earth, his eyes like two small moons, his hands bloody, his shoulders trembling.

He looked at me with the despair of a lifetime, beyond what his brief years should have brought him. “You’re Akiba,” he said. “I’m Ben Zoma.”

The night air slid between my clothes and my body. I felt whole; more than whole, as if anything I wanted, I could take.

“I’m not Akiba. I’m just Marjorie. And you’re not insane. Not yet.”

Nathan let me button his coat. He looked at the wounds on his arm. “They’ll think I tried to kill myself.” I had concocted many theories about Nathan over the years, but the truth was simple. If it weren’t for Holly, and now Eli, Nathan’s life would be a desert of loneliness. He didn’t want to own her. He didn’t want to change her. He just wanted to be with her.

“You won’t tell anyone about tonight,” I instructed him. “And neither will I.”

WE STOOD IN SILENCE AT THE LAUNDRY ROOM SINK WHILE I tested the water temperature. Nathan pressed his bleeding arm against his chest, his opposite hand white-knuckled around the wound, rocking slightly back and forth as if he were praying. Maybe he was. His eyes were open, unblinking, blind.

“Hold it up,” I said. His eyes darted back and forth at the sound of my voice. “Hold it up,” I repeated, louder, raising my hand above my head. He mimicked me, showing an arm coated in blood down to the fingernails.

“The water’s okay now,” I said. He held his forearm under the faucet until the incisions became visible, clean and narrow but deep. Blood continued to seep from the wounds, steadily but not pulsing, and while I blotted the cuts with a clean towel, I scoured my mind for first-aid rules, television trauma scenes, anatomy lessons from the college biology course I had taken to fulfill a requirement. I wound gauze around his arm from the elbow to the wrist, tight and thick. It was the first time we had ever touched.

He was right—the emergency room doctors would immediately peg him as an attempted suicide. Holds, sedatives, endless interrogations. And the explanations he would give. He would never think to lie, and even Holly wouldn’t believe him.

I led Nathan into the living room, threw an old towel over the couch, and directed him to sit. “I’m going to get you clean clothes,” I said. He sat on the edge of the sofa, his gauze-sleeved arm held in front of him in an almost commanding gesture, but his eyes remained distant. “Hold it up,” I reminded him, and he lifted it slightly higher. The surface layer of the bandage was spotless. The bleeding had stopped, or at least slowed.

I rummaged through their dresser and tossed aside Holly’s clothes—rows of navy and black tights rolled into balls, skirts that unfolded to fall all the way to the ground, high-necked sweaters, nightgowns with long sleeves; the bottom drawer was stuffed with pink and purple tank tops, jeans with fashionable slashes in the thighs. Their closet contained cheap blazers and threadbare dress shirts, Nathan’s clothes, meant for synagogues and study halls. Holly’s lavender bathrobe was heaped in the corner, and beneath it, those red and black high heels, fifty dollars, creased from wear but still shining.

She hadn’t thrown any of it away.

I draped Holly’s bathrobe over Nathan’s shoulders. The gauze was still clean. I reached around to my back, and the ache where the White Rebbe had cut me sharpened into pain. My shirt was sticking to the tattoo, but it was dry, at least. My mortal blood hardening into something indelible.

I found the last sleeping pill. I had been so desperate for them but had taken none. I held the tablet, the size of a pencil eraser and the color of a tooth, up to the light. It did seem a little risky, mixing medication with blood loss, but he needed to rest, if only to put some distance between himself and the last week.

“Hold out your hand.” He did, and I dropped the pill into his palm.

He swallowed it without hesitation and lay down on his side, still obediently raising his bandaged arm perpendicular to his body. He was following my orders. His shivering slowed, and his lids shut, though I could see his eyes moving under them.

I sank into the armchair. My body ached—from cold, exhaustion, tension, the new wound in my back, maybe, though that pain was beginning to subside again. What came next? I could call my family, tell them I had found him, and that he was okay. But he wasn’t okay. He needed time to regain his composure. There would be questions I didn’t know how to answer, and there was still baby Eli, his diagnosis lingering in the unknown. No. It wasn’t over yet.

WHILE NATHAN SLEPT, I CLEANED. I STRAIGHTENED THE LIVING room. I scraped candle wax off the tables and got down on my belly to hunt loose scraps of paper, printed with words I couldn’t read. I went downstairs and gathered Nathan’s failed drawings of the letter. I went upstairs, collecting more of the fevered sketches from the nursery, more supplications and protections and commands pinned to the walls and tucked under the mattress. I found more slips of paper in the drawers beneath the changing table, between the undershirts and tiny socks, and once I was sure I had found them all, I went into the backyard. The first time the White Rebbe spoke to me, he told me not to throw away old books but to bury them, and Nathan’s writings deserved the same respect. I knelt and dug through the loose earth with my hands, scooping dirt away, the hole growing deeper and deeper until I could reach down nearly to my shoulder.

Books. I lifted one out of its grave. The warped cover was stained with soil, but the dirt slid off the gilded page edges. I opened to the first page, careful to keep the aged spine from breaking loose.

It was my book—the novel with the Wandering Jew and his ghost—but it wasn’t my copy. I flipped through the pages, sturdy despite their age and recent interment, and found an annotation, text lined with ink faded to lavender.

It is surprising that in all the Chronicles of past times, this remarkable Personage is never once mentioned. Fain would I recount to you his life; but unluckily, till after his death He was never known to have existed.

And there, on the flyleaf, my grandfather’s handwriting. I held the book to my face, blowing off the clinging dirt, afraid touching it would press the particle

s into the fiber and seal the words away from me.

The White Rebbe fled into the night.

Grandpa had read it after all, during those last years when the White Rebbe stories returned to him, the words so difficult to contain that he scrawled them in the margins of novels. Maybe I had seen this on his shelf years ago, and the title had stuck in my subconscious. Maybe I had told him about the novel in my dreams, and he had found a copy in the infinite library where he spent his death.

I wondered what he thought of it.

A car pulled into the driveway; doors opened and closed. It must be Holly. Eli was coming home tomorrow—no, today. It was morning. I had lost track of time. I laid the novel back into the pit, burying it, I hoped, for the final time.

I HAD EXPECTED AN ENTOURAGE, BUT IT WAS JUST MY PARENTS, Holly, and Eli. I supposed Nathan’s family had been chastened by his disappearance, my mother’s assume of command at the hospital, my own harsh words to Yael. Nathan was back, though, and there would be time to fix all that. When I came inside, he was sitting on the couch, kneading his hands. He looked up at me and nodded once, then wordlessly followed Holly upstairs, still in a daze. I went upstairs to scrub the dirt from under my fingernails and maybe borrow something to wear—my clothes were caked with dirt, a lot easier to explain than the bloodstains hidden beneath. Holly and Nathan were sitting on the edge of their bed, space enough for another person between them, looking at the ground and speaking quietly.

For now, I was glad just to have the six of us, alone at the house. Eli slept in his carrier on the kitchen table, while my mother made something to eat, finally having learned the reordered cabinets, which dishes to use, which to leave alone.

“Marjorie, tell me the truth,” Mom said, trying again. “Where was he?”

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses