- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

The Angel of Losses Page 21

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 21

We have arrived, the angel declares, his great voice hushed with awe and longing. The Sabbath River, on whose far banks thrive the Ten Lost Tribes.

Manasseh grows light-headed with joy: the dreams of the pious, the sweet yearnings of generations of sufferers, the redemption of a people nearly swallowed by mud are now in his sight.

How can we cross it? he asks. The river flows all day and all night except on the Sabbath, when it is forbidden to undertake a journey.

We must pray, the angel said.

Manasseh prays all his waking hours. He prays days into weeks. He maintains the posture of a saint, as if his stomach is filled with love of the Torah instead of twisted in hunger, as if he kneels in the soft hand of the Almighty instead of on desiccated earth, as if he is wrapped in a breeze scented by paradise, instead of a stinging, sand-flecked wind.

But Manasseh does feel the grinding of his insides and the thousand tiny mouths of the desert on his skin. When he can no longer bear the pain, he thinks of his father, instructing students in the library, and he thinks of his older brother, Solomon, gone he knows not where, but surely, surely to return and rejoin the family.

Manasseh pushes down his hunger and exhaustion and pain, a tiny pit growing ever heavier in the deepest part of himself, and prays until it seems the force of his concentration can ignite the world, a sphere of tinder since the day man fell and God estranged himself from creation. He prays to correct the greatest loss of all: to heal the world, to end it.

He prays for thirty-nine days, and on the fortieth, the Sabbath arrives. At the midnight hour, when the Messiah feasts and the dead rise to worship, Manasseh rises from his bed in the sand and comes to the arrested river, now a wall of boulders threaded with silver light. He walks until he finds a hole in the wall, a space where the fallen rocks allow a passage to other side, a hall glowing with mineral-reflected moonlight. And there, standing at the other end of this hall, is his older brother.

Solomon is dressed in a priestly robe and wears a metal breastplate emblazoned with the seal of the lost tribe of Reuben. He has changed since his flight from the village; he is taller, with dark eyes instead of light; his beard is reddish instead of brown.

He looks like Solomon, but he is not Solomon.

You have come for me, he says. Your brother.

You’re not my brother, Manasseh said. Though you have stolen his face.

I am your brother, the strange but familiar man replies.

It is impossible. Solomon set off in the opposite direction, and had no staff to guide him, Manasseh counters. How could he have found this place?

I am your oldest brother, born before Solomon, the stranger replies. When I was a baby I fell ill, and the Angel of Losses carried me to live among the lost souls of Israel. All this time, I’ve waited for you to find me. I am the firstborn; I am the next of the line. Bring me back.

Manasseh, finally at his life’s great goal, hesitates.

The angel appears beside him, blue-gray veins in motion under his skin, his eyes glinting red.

No man can end the exile and bring the Messiah, Manasseh says, repeating what he was taught by a father who hid so much: the nature of his unearthly power, the birth and death of an eldest son. Manasseh loves his father dearly, and he refuses to feel betrayed; instead, he has the sudden sense of how dangerous his own piety is, how it has, like a parasite, taken possession of every other faculty he possesses.

Only the Almighty can bring the redemption, Manasseh says. We must hope only that he hears our prayers and is merciful. No man can cross the river until that day.

And no man knows if today is that appointed day, Yode’a says. And no angel, either.

Manasseh’s heart lifts in his chest. He too often wondered upon waking if it might be the final day, the first day.

And no man knows how He intends the river to be breached, Yode’a continues. And no angel either.

Manasseh’s heart beats stronger. He believes he is intended for a great purpose, greater than performing wonders in a village of mud. It could be he who sets foot into the land beyond and reunites the nation, reunites the fallen world with paradise, reunites a people with its God; he who breaks the mystical balance that holds them separate, shatters the barrier that divides Israel, and first hears the thunder of the Ten Lost Tribes on horseback, leading the Messiah from oblivion.

Manasseh steps into the moonlit passage. His foot touches down on sand white and fine and cold as snow, and his robe and skin shine like ice. The great boulders of the Sabbath River are like the bellies of whales, barnacled by frost. Their shadows waver on the desert floor, caught in the tide of this second world. Manasseh’s breath emerges in a cloud before him, and as he steps forward, and forward again, the cloud expands, the great rocks shimmering. He continues through the field. Something has shifted—the straight corridor is closed, replaced by a labyrinth of boulders. He looks behind him and sees the same assembly of sparkling pillars.

Manasseh is frightened.

He tries to retrace his steps but only winds his way farther into the river. He pivots again. He no longer knows if he’s running toward the Lost Tribes or away from them, because yes, he is running now, heaving great plumes of vapor, enveloping himself in his own fear. The sand is so cold that it burns his feet. The rocks slash his fingers as they reach for support. Above him the stars swirl, offering no guidepost—or is it he who is spinning, caught in the winds between worlds?

He tries to stand still, but his body will not speak to him. He does not know if he is stumbling forward or hunkered down in an unsettled space; if a storm is battering him or if he is throwing himself against the wintry air. Above him, the wisps of cloud tint pink. The sun is beginning to rise. The Sabbath is ending. The rocks hum and then rumble and then lift off the sand. The river once again takes flight.

Manasseh squeezes his eyes shut, covers his ears, braces himself. When he opens them again he sees—

MANASSEH’S CRIES RISE ALL THE WAY TO THE CELESTIAL academy; they wake the patriarchs from their slumber, disturb the prophets’ lectures, interrupt the famous rabbis’ debates. The great souls weep for the young man’s suffering, and the suffering of their people, but all of their tears will not amount to those of the lonely angel, invisible on the other side of their impenetrable windows.

In the eternal library, a reader watches the letters tangle on his page. A new sentence is born before him:

No man can end the exile, and any who tries is doomed.

And the Sabbath Light still tethers Manasseh’s body to life, even as the petals of his mind fall away, exposing the shape of the great letter, free to be plucked by whoever dares to claim it.

THE WHITE REBBE, AWAKE IN THE BLUE DAWN, REMEMBERED the Talmud’s declaration: A dream left uninterpreted is like a letter unread. He went to his school to await his students’ arrival. The little black dog was sleeping on the stoop, and when he approached, it stood and gazed upon him. He took its furry jaw in his hands and peered into its eyes—black mirrors, simultaneously blind and all-seeing. They reflected the White Rebbe’s face twice: the face of an old man. For a moment he imagined he saw with the eyes of the Angel of Death himself.

The White Rebbe was afraid—but not of death, and not for himself. He feared for his son and his grandson, who, after his passing, would receive an inheritance he did not wish to bequeath—a visit from the Angel of Losses. The angel was not a benevolent divinity, sent to aid pious villagers with their earthly woes. Yode’a did not care for their trials or triumphs. He wanted only to return the Sabbath Light to its source in paradise and thereby undo the Berukhim Rebbes’ theft of his magic, to end his own exile from God.

The angel wanted to force the Messiah’s premature return and unite the lands on either side of the Sabbath River—but the Law would not allow it, and any who tried would suffer. And should, by some flaw in the design, one succeed, he would bring the end of time.

The White Rebbe understood now that the men of his family were

not scholar-mayors, chosen to be small granters of small wishes. They were holy fools at best, blasphemous strivers at worst. The angel would taunt his sons, just as he did the White Rebbe’s father with the death of his firstborn, never to be spoken of again, and the dire illness of his second; just as he did the White Rebbe himself, with hints of his family’s mortality and promises of fame.

If only, the White Rebbe thought, if only my father and I had been learned in one more language, that between father and son. If only he had told me the truth.

The White Rebbe felt responsible for what had become of Manasseh. His father had tried to tell him: Manasseh was too holy, or perhaps too naïve, to resist the angel’s temptation. He was responsible now too for his son, who looked so much like the rebbe’s wife. He realized that the secret letter, the source of his family’s holy power, wasn’t a gift passed from honorable father to dutiful son. It was a trap, a totem clung to by desperate men. Desperate men like himself.

But he was different, a special man, one of the tzaddiks of history. He was stronger than his fathers. He was the strongest. The angel himself had been telling him so for years. Not strong enough to breach the River of Stones—no man was—but perhaps strong enough to outrun the Angel of Losses himself. Perhaps.

The burden must be his, not his son’s, not his grandson’s. As long as he lived, the secret letter of the Messiah and the dead in paradise, the letter that completes the one immutable name, would be his; as long as the Sabbath Light burned in his flesh, his children, their children, and their children, would be ignorant. They would live and they would die. They would be free.

Eleven

On the loneliest nights of my childhood, tucked into my own bed in my own house, Holly asleep just across from me and my parents just down the hall, I found myself wishing to go home. Desperately, stupidly, for if I wasn’t home, where was I? And as an adult I tried to cure that same persistent, unnamable homesickness by going back to my childhood home, but the feeling always remained.

It wasn’t until I closed the covers on the last notebook—after everything I knew had stopped being true, and the very earth I clung to had shifted, floated through its atmosphere, locked itself into a new groove—that I understood that all of those earlier moments had been glimpses of my future, practice for this very moment, practice for the most important trip I would ever take. It was time to go home.

I felt like Manasseh, just before he lost his mind—the earth around him rumbling and rising into the air until he was caught in a current of boulders. It all seemed real to me: the seam between the living and dead, the geography of the end of time, and the urgency of ageless questions. Where did one find the River of Stones, and what would it take to cross it? Was the old man haunting my footsteps, or was I haunting Grandpa’s, following the trail he had left across Europe to recover everything he had tried to abandon?

All along I had thought that if only I found all of Grandpa’s White Rebbe stories, and deciphered their hidden meaning, I would be able to understand something and then know what to do about everything. But there was no puzzle, no key—just a man who had fled the burden of his own history, who had chosen himself over his brother and was condemned never to speak an honest word to the people he loved.

Part of me knew it was unfair to judge Grandpa—I’d never lived through a war. But that was the point. Holly and I weren’t at war. We were a family. It was so easy for me to do the right thing.

Solomon was ready to let the Sabbath Light go, and he no longer cared who inherited it, but I still did. It wasn’t that Nathan was untrustworthy, unfit—or that I wanted a last chance to beat him at some game. Grandpa had lied to me about who I was. There was a part of me that was missing, and I had to take it back, before Nathan took it from me.

I kept thinking about Nathan’s penultimate entry in the map, how he must find the last of the line, and about the smooth stones lined up on my grandfather’s grave. The Berukhim Penitents meditated by the tombs of the rabbis to receive their wisdom. Nathan thought Grandpa was one of these holy men.

He was going to summon my grandfather, the last soul who might tell him how to win the White Rebbe’s favor and receive his magic. And if he could call Grandpa down from that room where we met in my dreams, then Grandpa would help him. He would sacrifice Nathan in an instant to stop me from doing what he could not bring himself to do.

Nathan was prepared to destroy himself to save his son, but he still wanted someone to know what happened to him, and why. Of course, there must be a number of places where he could have safely hidden the last notebook for me. The only reason to leave it with Sam, I thought, was to distract me, to send me on a journey hours south and hours back again, to buy more time.

I went straight from Brooklyn to Penn Station, and arrived with ten minutes to spare before the next train to New Jersey. I went above ground and called Simon.

“You won’t tell me what you found in Brooklyn. You won’t tell me how you’re going to find Nathan,” he said. “And you don’t want me to come with you.”

“When I come back,” I said. “It will be different.”

“I don’t believe you.”

I was so angry with Grandpa for keeping secrets from me, yet I was keeping secrets too. And just like the White Rebbe, I thought that it was okay to take the risks that had ruined those who had come before me, because I believed—as they had done—that I was different from them.

I had to believe that. My choice was no choice at all.

“I’ll come back,” I said. “It will be different.” Silence. “Please, say something. The train is going to board any minute.” Still, he said nothing. “I’m sorry,” I said, and hung up the phone.

IT WAS DARK WHEN I ARRIVED AT OUR OLD STOP. I BEGAN THE long walk across town to the house, where I hoped to find the spare keys to the car Nathan had left in the driveway and continue on to the cemetery. The scattered streetlights came on, casting chalky glows on the pavement, and the mounds of fallen autumn leaves released the sweet scent of rot. I had been alone with my thoughts for hours. Now I wondered, why shouldn’t Nathan have the Sabbath Light? The Berukhim Rebbe was his master, and Eli his son. Why shouldn’t I let Grandpa inscribe his past, all the generations of our family, inside a few bedtime stories, a few flimsy notebooks bequeathed to a landfill?

For a minute I indulged the fantasy, returning to my life as it was before the White Rebbe and the Sabbath Light. But as I turned down my old street, I saw a flash of light in our otherwise dark and shuttered house. The driveway was empty, the windows opaque, except for a single square of backlit curtain on the second story. Eli’s room.

I unlocked the front door, and the profound stillness of the house amplified the workings of my body—my pulse, my buzzing eardrums, my fiery brain. I flipped the light switch in the foyer, but the starkness of the light only deepened the shadows at the top of the stairs. “Nathan?” I called. No answer. For months Nathan had made me feel like an interloper in my own home; now I drew on that old resentment to overcome my fear of what state I would find him in and shut the door behind me.

I flicked the light switch at the bottom of the stairs, but the landing remained dark. I stepped up and up again until the darkness began to thin with a glow from the end of the hall. Maybe I hadn’t really seen the bedroom light blink on; maybe I had simply forgotten to turn it off during my last visit. I paused outside the door to the room. On the other side, the floor creaked.

I took a deep breath and nudged the door open. The nursery was gone. The walls rippled with book spines, brown and navy and maroon, leather and canvas and snake-slick paper. Grandpa’s desk with its glass surface and spindly legs and baroque knees stood in its appointed place beneath the windows; his stack of magazines leaned against a wall; his desk lamp gave off a soft green light.

And there, in his chair with the flattened pillows tied to the seat and back, sat the old man, his spine curved as he leaned over the desk, his white hair wild as he scribbled in a steno pad. H

e lifted his head and closed the notebook. He shifted in his chair to face me.

“Grandpa.”

“I never wanted you to find me here,” he said. “But I’m so happy to see your face.”

I crossed the room and kneeled before him, laying my cheek on his lap. I closed my eyes and memorized the feel of his hand stroking my hair. I knew we would not see each other again.

“I thought I could protect you,” he said.

“From your uncle? From the angel?”

“From all of it. Our suffering. My suffering. I wanted you to be free.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. The notebook on the desk was open, blank except for the title. The Death of the White Rebbe. “I’m not afraid of any angel.”

He touched my chin and I looked up into his eyes, crinkled in a sad smile.

He wasn’t the bitter old man from Brooklyn, or the traumatized boy from Russia, or the guilt-stricken author of the rebbe’s tales. He was my grandpa, the man who sat by my bedside, crafting simple tales of heroism and magic in his perfect American accent. That was the man he always wanted to be, and that’s who he was, first and foremost, in my memory. “I have hope for you,” Grandpa said. “For you and Holly.”

A wave of shame took me. “I don’t know why I treated her so badly,” I said. I no longer understood my compulsive need to argue and win, or that long-held conviction that I knew her better than she knew herself. It was harder, I saw now, to hold on than to let go.

I rested my cheek on his knee again, the bone hard against my temple. He patted the back of my neck. It felt so real. It was real. Soon it would be over, and if I dreamed of him again, he would just be the echo in my memory, a mask of my subconscious, a photo image slowly fading to white.

Soft footsteps sounded. I followed Grandpa’s gaze to the new doorway in the back wall, a thicket of shadows where the sky over our backyard should have been. The footsteps grew louder, and with them came a ragged, labored breathing. A boy appeared, shrouded in an oversized coat. His body trembled with each breath. He opened his mouth and coughed.

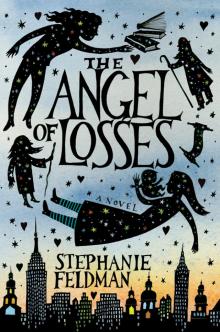

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses