- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

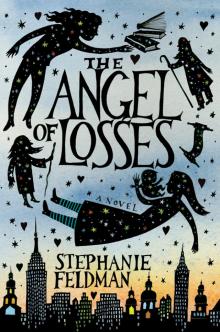

The Angel of Losses Page 15

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 15

Now he has both hands on my face and I want him to let go, but he is speaking still.

I’m begging you. Don’t make my sin be for nothing.

I WOKE TO DARKNESS. I LAID MY PALM ON MY CHEEK, OVER THE ghost of Grandpa’s touch, and then curled my fingernails into my skin until it hurt. My dreams of him usually left an ache in me, a bruise awakened on the inside of my ribs. But now I felt something different, something cold and hard, a fist squeezing shut. Anger at him for his cruel words, and for leaving me a second time, now, when I needed his guidance most.

I had to get out of the apartment. When the sun rose, I went to the student center and claimed one of the public computers by the window. I searched for an obituary for Grandpa’s friend Sam—I hoped it would list his children and grandchildren, some clues on how to find them. They probably had nothing to tell me, but I needed to be sure.

I hadn’t considered the sheer number of Sam Cohens of that generation in New York. I found several death notices, but one featured a photo of a different man, a second described a bachelor, a third listed a death that was too recent, a fourth a neighborhood too far away from the senior center.

Maybe my father was wrong. He had been wrong about the notebooks. Sam could still be alive. He could know something. I was grasping, I knew, but nonetheless.

A cloud passed, and the windows of the science building across the courtyard glinted like ice in the sun. I shaded my eyes—and there he was, the old man, rising from a bench, a book in his hands.

I threw the strap of my bag over my shoulder and ran outside, but as soon as I got outside, the canvas vibrated against my ribs—my phone was ringing. I dug inside, feeling past the books and pens and ChapStick. The screen lit up with Mom’s number.

“Hello?” I said. The old man was gone. I had only looked away for an instant.

“I’ve been calling and calling,” she said.

“Sorry, I guess it was on silent.” I spun in a circle, finally spotting him slipping through the gates and onto Broadway.

“Eli’s in the hospital.”

“What?” I pushed through the crowds of students.

“He had another seizure. This morning.”

I stopped at the curb just as a truck rumbled by, empty and shaking on its carriage. It seemed as if my whole body reverberated in its wake, and it was several moments before I felt still again.

It took twenty minutes to get Yael on the phone. She told me not to come, not yet—the doctors at the local hospital were talking about transferring Eli to Manhattan, the best pediatric unit in the region, and I could meet Holly and Nathan there. It was another hour before they made the decision and the arrangements and put my sister and her baby in an ambulance to New York—another forty-five minutes before they would arrive, so I let the crosstown bus go by and walked through the park.

It was a beautiful day. There were just a few white clouds painted above the gold and rust trees. No sounds of traffic, just lingering birds, a few dogs, mothers and nannies pushing strollers, watching small children in new coats tumble across the lawns.

Eli was dying. The thought came to me like something out of time—like a foreign word I had been staring at, whose meaning had just been revealed.

The hospital was a huge complex squatting on a full city block. There was an atrium in the center, where people sat on benches beneath a glass ceiling, amid small trees that could have been fake or real, and a café cart with a line of customers snaking through the hallway. The building was new, but still the air had a chlorinated scent, and the PA system crackled along the ceiling.

I took the elevator to Pediatrics. When I gave the receptionist Eli’s name, she frowned at me. “Are you family?” Her voice was skeptical. I didn’t look like the others I found in the waiting room at the end of the hall: Nathan’s brother, his mother in her stiff wig, two young boys with curls at their ears.

I was grateful when Yael appeared by my side. “They’re in the pediatric ICU,” she said quietly. “We can’t see him yet.”

I had never been inside an intensive care unit, but it seemed like a horrible place to leave a baby. I imagined Eli in a little glass terrarium, tubes taped to his skin with white circles. Yael started digging in her purse and took out a packet of Kleenex. She handed it to me. I realized I was crying.

My phone buzzed. It was Simon. “I have to take this,” I said. She pointed down the hall—the signs around us banned cell phones, but there was a designated space that way. “I’ll be right back.”

I hurried past open doors, the occasional flash of color from balloons or a jacket draped over an empty chair, trying not to look at the beds inside. The end of the corridor was awash in natural light, a small sitting room overlooking the atrium.

“Do you want me to come?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “I really do.”

I told him where to find me and hung up. Below, people were scattered across the benches, talking on cell phones; a doctor was reading a newspaper, and an old man with a dark hat and coat sat alone. He looked up into the light. And then at me.

I ran to the elevator. The old man kept appearing and disappearing, and I had to find him before he was gone again. But when the doors slid open at the first floor, there was my sister, all dark hair and gray skin. She didn’t move. I stepped into the hall beside her. She looked at the floor. Finally I reached out to her, put my hand on her arm, and pulled her to me. She laid her head on my shoulder and her body began to tremble and I locked my arms as if she might slip through them, collapse, give up.

Holly pulled away, put her hands over her face, rubbing her skin so hard I cringed, and then took them away and shook out her hair. “For a minute I felt like I could just leave,” she said. Her voice was thick from crying. “I could get on the train and go home and Mom and Dad would be there, and Grandpa, and you. And I could be in high school. Or a little kid. Or not even be in the world at all.”

We moved to the side to make room for people passing in the corridor. All the doctors and nurses in scrubs looked so young, too young to know all they needed to take care of the people here. I gave her the packet of tissues. She wiped her eyes, and as soon as she took the tissue away, they were leaking again.

“Were you escaping too?” she asked.

“I was looking for you,” I said.

“The counselor gave me this,” she said. “It doesn’t make any sense.” She presented a crumpled pamphlet. I unfolded it. A single word stretched across the pale green panel, a single word the length of the alphabet, a name that encompassed the whole world.

“Is this what they think he has?” I asked.

“We have to wait for the tests.” She shook her head. “Marjorie, it’s recessive. One in twenty thousand.” I opened the pamphlet and saw a bullet list of symptoms—seizures, jaundice, missed milestones, and strikingly bright blue eyes that never fade—and closed my fist, crumpling it along the seams Holly had created. “They test for it, but they never tested me because I wasn’t born Jewish.”

She looked at me with such desperation, and I was so sorry for Holly and so angry at Grandpa. If he had told the truth—but he didn’t. This was his fault.

“Grandpa was Jewish,” I told her. “I’m sure of it.” I was so consumed by the mystery of the White Rebbe’s bargain, so dizzied by the old man’s manipulation and the angel’s cries, so troubled by Josef—why his existence was a secret, and what had become of him—that I had treated Grandpa’s Jewishness as a biographical footnote. I hadn’t paused to consider what it meant for Holly, or for me.

She narrowed her eyes—a reflex, her habitual contempt for me—but when she spoke, her voice trembled. “Why would you say that?”

“It’s in the notebooks.”

She crossed her arms and studied the floor. “It doesn’t matter.”

“Of course it matters,” I said. It prefigured Holly’s whole life: Nathan, her conversion, even Eli’s illness, if the projected diagnosis was correct. It suggested a history

to fill in Grandpa’s life before New York. He must have escaped during the war.

“All that matters is my baby,” Holly said, and she began to cry again. I put my arms around her, and she leaned her whole weight against me. We stood there in the corner of the passage, the only part of the complex that remained in the shadows, and in all that time, Nathan didn’t come to look for her, and I didn’t ask where he was.

SOON HOLLY RETURNED TO ELI, AND I CONTINUED ON TO THE atrium, but the old man was no longer there. When Simon arrived, I was alone in the lobby, grinding my teeth to dust. Eli’s disease was connected to Grandpa, but not just by DNA. The White Rebbe nearly died from convulsions as a baby, and the Angel of Losses had given his father the power to heal him. The White Rebbe had lost a little brother, just like Grandpa had.

Then there was the old man. He knew about Grandpa’s past, and he knew about my future; he had given me a charm to protect Eli, before any of us could have guessed his fate.

Maybe he knew how to save him too.

“Have you eaten?” Simon asked.

“Not since this morning.” I had grown increasingly queasy all day—maybe some of it was hunger. We went outside to find a sandwich.

“I looked it up on the Internet,” he confessed. “It’s like Tay-Sachs, but it’s more rare.”

“Did you print anything?”

He shook his head. “I was going to, but it was all too terrible.” He paused. “You should get tested to see if you’re a carrier.”

I shuddered. “I can’t think about that right now.” Not the test—the idea that I could ever put myself into this drama Holly was living, ever let anyone get me pregnant.

“Maybe we should go back inside,” Simon said. “So he’s not alone.”

“He’s not. Holly’s with Eli.”

“I was talking about Nathan,” he said.

There he was beyond the rotating glass doors, like a dark imperfection inside a transparent machine, or the family curse brooding deep within the spun glass of Grandpa’s autobiography. Grandpa had walked across Europe to shed the truth, and he would have succeeded, if not for Nathan and the corresponding defect in his blood.

Simon agreed to wait—I needed to speak to Nathan alone. Nathan stood inside a ring of plastic trees, staring into the skylight hanging three stories above. He didn’t stir at my approach, and not thinking, I reached out and touched his sleeve. He flinched; I flinched. “Nathan,” I said. “I’m so, so sorry—”

“We need to find the other stories.” His eyes were bloodshot raw, more red than white, and I winced as he trained them on me.

“There are two left,” I said. “Four total. The White Rebbe and the Angel of Losses and The White Rebbe and the Ghetto. But I don’t know where to look anymore.”

A few pigeons flapped overhead, coming to rest in the metal rafters, and we both looked up. Dark gray clouds were sinking against the glass, closing us in.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “I already know what to do. Whatever happens after that—I don’t care.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked. “What are you going to do?”

“Listen. Chava has been mad at you a long time,” Nathan said, knocking the little bit of breath out of my paper lungs. “I told her she needs to forgive you. She’s going to need you if I leave.”

“Leave for where?” I asked, my voice grave, but not grave enough to touch him. He was burning into bronze in the fire of his own single-mindedness. Any force would glance off him; he would feel nothing.

HOURS LATER, WHEN MY MOTHER ARRIVED FROM THE AIRPORT, she immediately began begging Holly to go home.

“I can sleep here,” Holly protested. “I need to feed him.”

“When did you last sleep longer than an hour?” Mom asked, glancing worriedly at Nathan, who still said nothing. I tried to catch his eye, but he refused to look at me. “You’re making yourself sick.”

“I don’t care,” Holly said, her voice so flat it frightened me. My mother hadn’t been exaggerating about her insomnia.

“Mom can stay with Eli,” I said. “My apartment is only ten minutes away.”

“Nathan and I can’t stay there,” she said. “We’ll stay with his parents.” She took his hand, and still he said nothing. Simon had edged away from the conversation, suddenly tense. He had stayed with us all day.

“It’s ten minutes,” Nathan said finally. “You stay in the city.” I had always imagined the two of us struggling over ownership of Holly. Now he was giving her to me. It indicated a new understanding between us, maybe, but it also worried me. “I need to get some things from the house anyway.”

Holly reached for her husband and then lost the will, her fingers just brushing his sleeve. “But Yael took the car home,” she said softly.

He lifted his chin. “He can drive me.”

We all turned to look at Simon. His eyes grew wide. He cleared his throat. “Sure.”

“You don’t have to,” I said. “You’re probably busy.”

“It’s okay,” Simon said. “I don’t mind.”

Nathan leaned into Holly, murmuring something about saying good-bye to his family, before marching away from us without a glance back.

I went with Simon to get the car. He tossed his keys, up and down, and I took his wrist. “What are you, some kind of saint?” I asked.

“It’s not a big deal.” I started to speak but he interrupted me. “I mean, Christ. It’s nothing.”

“So I guess this was the worst possible time for us to meet,” I said. “Family tragedy. Et cetera.”

He kissed me. “Or just the right time.”

I wanted to promise that we could hole up in his apartment—not talk to my family, not open my books or his maps, forget about the Angel of Losses and the White Rebbe. We could move to Mexico and disappear among the Jewish Indians. But all those suggestions had to follow “when this is over.” And “when this is over” meant “when Eli is gone.” Like at the end of my grandfather’s life, when we couldn’t make plans, couldn’t leave town. He was finished living, and we had to wait with him for the end. His body persisted, his rational mind and memories in place, but his soul wandered far.

“Something’s going on with Nathan,” I said. “Let me know if he says anything—anything I should know.”

Simon nodded, but I didn’t think he understood.

“Anything at all. I mean, tell me everything.”

He nodded again and we said good-bye. I walked across the parking lot, sparks of anxiety accumulating around me—just a knick of friction, and I would shoot through space, striking anything that reached toward me.

BACK AT MY STUDIO, I GAVE HOLLY ONE OF THE SLEEPING PILLS I had bought the night I first saw the old man downtown.

“Marjorie,” she said. “I love him more than anything in the world.”

I understood her first attempts to describe her love for Eli: a feeling so strong she could barely hold it in her body. Compressed ferocity, ever on the verge of eruption. I smoothed her hair back. “He’s going to be fine,” I promised. He would be. Somehow, I would make sure of it.

THE NEXT DAY AT THE HOSPITAL, HOLLY SPENT THE MORNING IN and out of the specialists’ offices while Mom held the baby in the PICU. When Holly saw me coming, she would turn into the corner, pressing both hands against her ears, murmuring into the phone. I wondered who she was speaking to, but for the first time in a long time I didn’t take it personally. Nathan was supposed to meet us here this morning, but he had never arrived.

After a few hours, I was allowed in to relieve my mother. The nurses wrapped me in sea-green paper and led me among the glass cubes. Some of the babies were so small—hairless, their limbs like fingers, their rib cages flexing as they breathed. Next to them, Eli looked healthy and fat, his bright blue eyes sliding in his head. He didn’t care, of course, that his father was gone—maybe Nathan’s familiar presence brought him a kind of comfort that mine or my mother’s couldn’t, but surely not more than Holly’s did. E

li’s life was just sensation—hunger or fullness, pain or not pain, sleep or the blurry world of wakefulness. Maybe he dreamed. Maybe his dreams were crystal clear. I wished that I had something to give him, like the old man’s charm, now strung through his mobile. But that meant nothing to him either—too hard, the chain something that might strangle, bind him.

I held my hand, hovering, above Eli, but he didn’t reach to swat it. I took his hand, his fingers stretching a quarter way across my palm. He squeezed. His fingernails were sharp, flakes of glass.

I heard footsteps and looked up. The nurse was leading an elderly man with a paper mask to the next station. He could be sick; I instinctively, uselessly, shielded Eli’s face. The old man sat beside the baby, put his hand on the incubator, and chanted something in another language. The nurse touched his shoulder, smiled, and walked away again. That smile. They must teach it in nursing school. Or was it something you had to be born with? A gesture of kindness that somehow acknowledged all of a person’s pain.

I had to restrain myself from asking the gentle woman to kindly leave and shut the door behind her. The old man and I had a lot to talk about.

“Eli looks peaceful,” the old man said, pulling away the paper mask.

He reached out and I shrank back in the chair, pulling Eli into the hollow of my stomach. The old man looked at me sharply and took his hand back into his lap. “What did you do to that boy?” I asked. His touch may have been a curse; but then again, it may have been a blessing.

He turned again, slowly, graced the glass with his fingertips. “I can’t help him. I don’t know how. I’ve outlived that good part of myself.” He looked at Eli, asleep in my arms. “But there’s a way to heal him yet.”

“How?” I asked, my voice a whisper. I coughed. “Is it in Grandpa’s notebook?” Machines beeped in the silence. Finally he said, “People once walked incalculable miles to beg my help. And yet here I am, before you, and you talk only about a senile old man’s ramblings.”

“You can’t talk about my grandfather that way.” My voice trembled with anger. Grandpa had said I was like him. Passionate. A survivor. How naïve I had been never to have done the math, to figure that what he had survived had been the Second World War—or perhaps, how unconsciously careful to collude with him in erasing the horror it suggested.

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses