- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

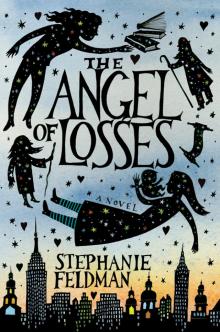

The Angel of Losses Page 14

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 14

The White Rebbe fled into the night. He looked for holy men, gurus, miracle workers, for he knew every powerful man has a source, and every angel has a flaw in its armor. He looked for his children, his children’s children, and their children, and theirs, strangers to him now, separated by thousands of miles and years, unaware of one another’s existence. He brought them gifts and bewitchments, and they greeted him as a lost uncle, a distant cousin. They knew the names of the Berukhim Rebbes, their wives and sons, and then one day they didn’t; they knew the wondrous feats of their ancestors, and then one day they didn’t; they had heard of a White Rebbe, yes, fairy tales, children’s stories.

The White Rebbe fled into the night. Everywhere were signs of the Angel of Losses. His watery footprints, the smoky breath of his wings, the fiery light of his eyes, and then his voice, his whispers of devotion, his promises of reunion, his prayers for his love. The angel was his shadow and his enemy, the source of his power and its end.

Everywhere the rebbe saw that invisible path, the one that lifted off the earth and wound toward a river of boulders, a river that hid the dead, and he turned the other way, and the Sabbath Light stretched an inch longer, a painful thread of infection, slowed by magic and yet inevitable. The longer the letter burned in his skin, the deeper its light penetrated him; the brighter it stained his bones, the stronger the scent of paradise on the wind, the more beautiful the distant clatter of stone. He was preoccupied with the forbidden river. If the angel were to catch him, the rebbe would not be able to resist his promise. He would once again let those wings encircle him, and carry him to an oblivion from which there would be no rescue. There were no more Berukhim Rebbes awaiting their chance for wonder. There was no mystic among his descendants who would recognize an angel in front of him, or sacrifice himself for old Solomon as young Solomon sacrificed for Manasseh.

The White Rebbe fled into the night. He walked across mountains and valleys and oceans and deserts and islands and continents. He walked through the city gates, and the celestial academy’s forgotten passageways, and he conjured a small, crooked house, and opened a gray wooden door. His steps slowed. He came to a stop. He looked around him. He stood in an alcove with a desk lit by a single, thick candle, and two armchairs buttressed with books.

He decided to rest here, in Europe’s Jerusalem, where the people cared only for the law, and had driven out the mystics and penitents, where politics overshadowed the old folktales. He lived according to the dream he had had as a youth, and worked as a scribe, drawing marriage contracts and prayer scrolls. The only wonder was in the loveliness of his handwriting, and the Sabbath Light grew small as a distant star.

Then the war came. The old quarter of the city became a ghetto, and humanity swelled against its gates, shouting, crying, lamenting.

Arise! The penitents—newly arrived, or newly initiated—wailed at midnight. Arise! The lament awakened a twin desperation in the rebbe’s heart, and that desperation sank deep inside his petrified soul until it met a hand reaching upward, a woman’s hand, warm as the lagoon on a summer night. He heard a voice inside his head, the voice of his wife, ensouled in his memory. Find another, she said. And come home to me.

I will find another, the White Rebbe said, and come home to you, and with those words the Sabbath Light flamed anew.

The Angel of Losses heard him. With one set of eyes, the angel looked upon the men of the world, and with another set of eyes, he looked upon their hearts, where their many lives are written. He found two of the rebbe’s lost sons, the brothers Eli and Josef, clutching each other inside the hand of Russia’s meanest winter. Eli was older, nearly a man, while Josef was still a child, clinging to his brother in his sleep. They were orphans. But Yode’a’s ministry included lost souls, and he would reunite them with their family. He would reunite them with the fate that coursed in their veins: to walk across the earth until they found its end.

While they slept, the angel carried them from their roadside bed to the city where the White Rebbe guarded his flame. And so the brothers were found. And so one was to lose again; and so one was to be lost.

I TUCKED THE BOOK AWAY IN MY BAG AND LEFT MY CARREL. I left the library. I left campus.

Eli and Josef, I thought. Eli and Josef. Eli and Josef.

I began walking south. I traveled the length of the island, past endless banks and drugstores, hardware stores and bodegas, overpriced restaurants with customers corralled outside, apartment buildings growing ever taller and glossier, public housing and what used to be public housing, until I reached the last park before the river. I had walked less than ten miles on a sunny day in a safe and wealthy city, and my legs ached from the exertion. I sat by the concrete bike paths and looked out at the pier.

Eli and Josef. Eli and Josef. Eli and Josef.

The sky had fattened to a rich blue. The sun was setting earlier every day. The river was lined with an iron fence and old-fashioned streetlights, and people were jogging and riding their bikes in orderly rows along the path. In the distance, boats sat on the still water, and beyond them, banks of brick and trees; and to the south, the Statue of Liberty, like a toy among the clouds.

I felt like I was on a very particular piece of the world—like a map Simon could load onto his screen. Grandpa had crossed from one map to another, and transformed the White Rebbe into the White Magician, in order to bring him along. He couldn’t bear to leave him behind.

But had he left a brother, Josef? I had never heard that name before. He always claimed to be an only child. He had lied to all of us. He had lied to me. He had lied about everything.

Eli and Josef. Eli and Josef. Eli and Josef, again.

AN ALARM CUT THROUGH MY SLEEP. SOMEONE WAS BUZZING MY intercom. The bell sounded a second time, and I dragged myself to the door. I hit the speaker and static flooded the room.

“Hello?”

A whisper broadcast into my apartment. “Arise . . .”

“Hello?” I snapped. It was three in the morning, a weeknight.

“She is in exile!” the voice cried through the static. A man, desperate and hoarse. “She is in exile! The holy house of Israel is burning!”

I recognized the voice. It was the same one I had heard that night at Simon’s, the same voice I had followed out into the street. I couldn’t think; I was too overwhelmed. I had been thrust into a story I didn’t understand, and I was angry.

I put my mouth against the intercom and screamed at the angel. “Go away!” My breath tasted like ash. I took my hands away from the button and listened to my pulse trip in my ears. I turned on the speaker again; now there was only the rush of the downpour. I drew back the curtain, but my window looked onto Amsterdam, and the front door was on the other side of the building, on 112th Street. The avenue was empty, the pavement alive with falling rain.

I got back into bed and stared up toward the invisible ceiling. I could feel my veins constricting, my blood swelling. It was a nightmare, I told myself. I was still half asleep when I jumped out of bed. But the bitter scent in the air, the exhale of a cheap, extinguished match, argued otherwise. School had taught me to deconstruct the supernatural, see through the shrouds to the Freudian repression and metaphors of social transgression underneath. But this was no intellectual exercise. A real creature was haunting me.

My anger was snuffed out, and I felt the fear that had smoldered beneath all along. I should call Holly, I thought, my brain unloosed in time, as if we were girls with a Ouija board, not a madwoman in a studio apartment and a wife who had traded ghost stories for God. It was becoming clear to me that if anyone was going to help me—explain what was happening, exorcise the angel—it was the strange old man.

At the same time, I feared that seeking help from him would be like putting out a campfire with a tidal wave.

It was midnight. I logged on to the test server for Simon’s map. When I entered his password, multiple windows fanned across the screen. They had done a lot of work since I last saw it. An animated icon sat

in the top left corner, a black stick figure walking endlessly against the edge of the screen. I clicked on him and the windows resolved into a single spread, Mercator’s flat earth blanketed by a rainbow of pixels, a single map of the folkloristic, scientific, historical. I wasn’t sure what I would find, but I was hoping I could, like Nathan suggested, triangulate the answers that the missing notebooks concealed. Why had the Angel of Losses cursed the White Rebbe? What was the meaning of the Sabbath Light?

Who was Josef?

I zoomed in on Europe, hoping to identify the city the White Rebbe identified as a Jerusalem. The city my grandfather might have come from. The continent was a rash of multicolored stars. I didn’t know what the colors indicated, so I clicked on a random green icon. A text box popped up.

Warsaw, Poland, 1934: “A new illness was appearing among their children—the ‘Tee-Saxe’ malady, diagnosed in America—arrested development, children dying at age of two: hardly any case among Christians: explained as product of old worn-out race.” [Citation: Israel Cohen. Travels in Jewry.]

So this was the genetics layer of the map. I didn’t think that would help me. I noticed a mass of blue where Europe melted into Asia—that was the layer Simon and Nathan had been collaborating on. I began clicking through their work.

Amsterdam, 1650: “Lastly, all thinke, that part of the Ten Tribes dwell beyond the River Sabbathion.” [Citation: Manasseh ben Israel. Hope of Israel.]

I remembered Nathan’s analysis: the physical-metaphysical problem. They were adding the mythical River of Stones that divided our world from paradise to the mountain ranges and historical borders on the map, uniting two visions of the world on a single plane.

Another trail, in Africa, brought up a different source:

Apocryphal document from medieval priest and king, who ruled a Christian kingdom, placed the Sambatyon River in Ethiopia. Believed to have been inspired by the account of ninth-century traveler Eldad ben Mahli ha-Dani, who visited Jewish communities in Babylonia, North Africa, and Spain, claiming origin in the land of the Ten Lost Tribes in East Africa. [Citation: “Prester John.” Encyclopedia of Medieval Folklore.]

I clicked on the traveler’s name, and from him to another Wandering Jew, this time from the seventeenth century. He claimed to have seen the other side of the Sabbath River, and I scrolled down and down through his description.

There the Jews were ruled by twenty-four kings, and an emperor six yards tall who rode a leopard. Just as Nathan claimed, the Jews on the other side were wealthy. There were two harvests each year, two birthing seasons for their livestock. Their horses drank wine and ate cooked mutton. The army carried golden spears, and the people wore garments of silver and gold. Never black—they were in exile but not mourning. There was no crime and no illness. And there again was Daniel the Pious, whose daughters were so beautiful they had to wear veils in public, and there was his Sabbath Light, glowing on the screen, not like a midnight sun but like a light at the end of the hall, a candle flame behind a cracked door.

The Sabbath Light was linked; it appeared elsewhere on the map.

The Lost Tribes living beyond the Sambatyon possess a complete messianic Torah, written in a 23-letter alphabet instead of the 22-letter Hebrew alphabet of the fallen world. When the Messiah returns, he will bring this lost letter with him, restoring the Torah to its complete, pure state. The Berukhim Penitents call this letter the Sabbath Light. [Citation]

There was no link. I clicked the word again and again, but no source was embedded. I knew where it had come from, though. Nathan.

The Sabbath Light, the last letter of the alphabet, the letter that completes creation. It belonged to the other side, but the Berukhim Rebbes had taken possession of it—part of some illicit deal with the Angel of Losses. I felt the same rush of excitement that I did when I found a new piece for my research—the possibility, the sense that the story was about to mushroom into something greater.

But then it collapsed into a deep well within me. At the bottom was just a name, charged with foreboding and despair. Josef. He was the true missing piece. He was everything. He was the one I had to find.

THE FOLLOWING EVENING I CROSSED CAMPUS AND SAT ON THE front stoop of Simon’s building. The air was cool, autumnal, and as clear as water. The whole city felt alive, the blue night glowing at every corner, refusing to go into blackness. A tall figure came down the block, his hands in his pockets, his shoulders hunched, a messenger bag, filled with books, I was sure, at his hip.

I stood up, my arms crossed against my chest. “Hey,” I said.

Simon stopped, startled, and took the headphones out of his ears. “What are you doing here?”

“I come out at night,” I said. “If you invite me inside, I promise I won’t leave without saying good-bye.”

There was a purity about him, a purity about being together and not speaking, about lying with my cheek against his chest, my skin absorbing his heartbeat, the fundamental, wordless motion of living. My mind unwound along that peaceful horizon where sensation turned into sound, consciousness into unconsciousness. When my nightmares came back—if I heard cries on the street, saw the footprints of a bloody mourner—there would be this moment to hold in my memory. A timelessness interrupting my travels, a peace that waited for me while I was lost in the world. Even if he slept through it all, unwakeable, as a distant door creaked and footsteps approached on the tail of a candle flame, he would still be there beside me.

“I’ve been having these strange dreams about my grandfather,” I said. “I’ve had them ever since he died. In the dreams, he’s still dead and I’m still alive, but we get to meet. It’s like visiting someone in jail. There are rules. And time limits. But I get to see him again. He’s coming more and more.” It was the closest I had come to confessing to Simon—to anyone—the mystery of the White Rebbe and Grandpa’s past. Because that’s what was really disturbing my sleep: not a riddle, or the lost ending to a fairy tale, but the truth of where Grandpa came from, and my realization that though he had died, his story wasn’t over. It was going to end, somehow, with me.

“Were you close?”

“Yeah.”

“Well,” Simon said, as if that explained everything.

“It’s different. It’s not just my brain burning through my memories, or compensating for missing him. The dreams are too real, and too specific.”

“I feel like you’re going to answer your own question.” His hand traced a circle over my back, and when he brushed the tattoo, I felt a warmth over my heart. He had asked me what the tattoo was, and I told him it was a picture my grandfather had drawn long ago. Maybe that’s why he was sure that all this was nothing more than delayed grief.

“No,” I said quickly, afraid that if I stopped to breathe, to think, I would never be able to be honest. “I think he’s trying to tell me something. I mean . . . I don’t. Of course I don’t believe in that. But you know how people get messages from the dead in their dreams—don’t get on that plane, or tell your mother I love her?”

“So what message is he sending you?”

I thought about his final words in the last dream: Don’t trust him. He won’t help you. Instead, I said, “He used to tell us fairy tales, when we were little. And then I found these notebooks, just recently, but the stories in them are different.”

“How so?”

“They’re dark. The characters have different names.” They’re filled with ghosts and angels and mystical alphabets. They’re Jewish. Like him. Isn’t that where this hunt was leading me? “They’re just different,” I finished.

“If you examine the past, you find it’s never the way you remembered it. It’s better to leave it alone. Keep your memories the way they are.” He sounded like my father. But that kind of answer wasn’t acceptable, and Simon knew it.

“Memories aren’t the most important thing,” I persisted.

“Then what is?”

The truth, I thought. No matter how many stories you spin, some w

ords are indelible and some ghosts never rest.

Nine

Abook is open on the fake wood-grain surface. When Grandpa sees me, he closes it and lays his hands flat on its cover. Beside its spine lies a gleaming black rod, a pen the length of his arm. Was he reading, or was he writing?

He’s brought you here again, he says. He wants something from you.

He’s been following me, Grandpa, ever since you left.

Grandpa’s eyes narrow. The old man. No, it’s not he who has brought you here. He knows I hate him. It’s the other one.

The Angel of Losses, I say.

He is appealing to you. He is trying to show you the power you could have.

His eyes soften and he sits back. His fingers massage the cover of the book.

You’re right about your sister’s husband, he continues, and I think, he doesn’t want to say his name, he hates him that much, and I smell the curdled edge of his bitterness like smoke.

Your brother-in-law is a fool. Let him go to the angel, and his fate. Let him take our place.

The fluorescent light crackles. A slight breeze troubles the green vinyl leaves of the potted forest.

Our time is almost up, he says, and touches my cheek, his hand fluttering like a feather in the wind.

But I just found you, and you still haven’t explained anything.

There’s nothing to know.

There is, I insist. There’s Josef. What happened to Josef?

Don’t come here again, he says, and now he is angry. I feel my flesh shrink against my bones.

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses