- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

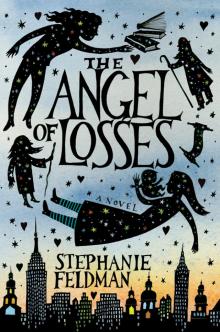

The Angel of Losses Page 9

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 9

He typed a few seconds and shook his head. “Nope. Sorry. What’s next?”

“The Sabbath Light.”

He entered it into the system and sighed. “Zero for two.”

I felt both disappointed and relieved. I needed to know more but also wanted to keep the White Rebbe for myself—just as I found myself both attracted to and repelled by the strange old man following me. His words were alternately inviting and hostile, and I couldn’t tell if he had been Grandpa’s friend or enemy. I should be wary of him, I told myself; any affection I felt was misplaced, only a by-product of his having known Grandpa, resembling him, even, just a little.

“One more?” I asked.

“Fire away.”

“The Angel of Losses.”

“Angel . . . of . . . Losses,” he said under his breath as he typed, and I grew queasy. It felt wrong—almost dangerous—to say the name out loud.

“Okay, one match,” he said. “Yad—wait. Yo-day-ah. I think that’s right.”

“That’s him!” I said. “What does it say?”

He glanced at me for an instant, then squinted at the screen, a little smile playing on his face. “He’s the guardian of the Sabbath River. That’s the river that separates the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel from the rest of the world.”

“Where did you find that?”

“Interview.” He sat back, crossed his arms. “We have a grad student collecting stories from different traditions. This one’s from . . . let’s see . . . They have a strange name. Something Penitents.”

“The Berukhim Penitents,” I said.

“Yes. How did you know?”

“My brother-in-law is one of them.”

“Ah,” Simon said, nodding slowly. He could hear in my voice that there was a story there I didn’t want to tell. “Well. I wish I could tell you more. I’ll keep looking. But if I’m remembering correctly, there won’t be too much. The Penitents tend not to talk about this stuff with outsiders.”

“Which stuff?” I asked.

“Angels. That’s the Berukhim thing, right? Invoking angels. Angel magic. Mystic . . . angel . . . stuff. If they’re the ones I’m thinking of, I mean.”

“So the Angel of Losses is theirs?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know for sure. The Sabbath River isn’t, though. That’s in a lot of stories. It’s a river made of stones that no one can cross except on the Sabbath, when it stops running. But it’s a sin to travel on the Sabbath, so you can’t cross it anyway. The Lost Tribes live in this fantastic land on the other side, and they won’t return to our world until the Messiah comes.”

“Is that what your map is of?” I asked. “The Sabbath River?”

“Well. Metaphorically.”

“Yes, of course, that’s what I meant,” I said. A little too forcefully. Metaphors, I told myself. Metaphors and symbols and devices. Russian fairy tales and Jewish legends, evolving side by side, fragments Grandpa absorbed during his secret childhood on the other side of the world. The more I searched, the more the magic of the notebooks would dissipate, my quest just a bit of anthropological scrabble. Grandpa would still be gone, and Holly would still be Chava, and I would still be alone with my books and my notes and my silly little ghost stories.

“So where did you find him? The Angel of Losses?” Simon asked. He was leaning back, one sneaker on the wastepaper basket, tapping a pencil against the desk absently. Simon put on a good show, I thought. Easygoing, unconcerned. But he was obsessed with his work. I knew that look—very well.

“My brother-in-law mentioned it. Something he’s studying,” I lied. “But there’s very little material on it, and their library—the library at their school—it’s limited, and he doesn’t have privileges anywhere else, so I told him I’d see what I could find here. Academic citizenship and scholarly brotherhood and so forth.”

“I’ll let you know if anything else like this comes my way,” Simon offered. “If you’d like. Academic citizenship. Et cetera.”

“Okay,” I agreed. “Thank you.”

He laced his fingers behind his head and raised his eyebrows, like he was waiting for me to say more. I shrugged. “Well.”

“Well.”

“Okay,” I said again, and my embarrassment at my awkwardness expanded inside me until there was no room for it left, and I started laughing, and Simon started laughing.

“Okay,” I said again. “I’m leaving now. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye, Marjorie,” he said.

I decided that I liked hearing him say my name, after all.

GRANDPA WAITS FOR ME AT THE SAME TABLE, HIS HANDS FOLDED on top of a book. I sit across from him. He knows I’m there but doesn’t look up. His knuckles, pale walnut shells, worry against one another as he fidgets. All around us fingertips murmur against paper. Readers sit in patched armchairs, plastic-covered couches, at laminate tables with foldout legs, their faces angled to the pages or moving in sudden flares of light, invisible.

The baby, he says.

The light shifts, and for an instant I feel the world has tipped. I look up, shielding my eyes against the light emanating from the ceiling, which is lost in a golden haze. A buzzer sounds, then static, a loudspeaker with no voice at the microphone.

The old man will tell you only he can help Holly’s boy, Grandpa says, taking my hands.

Help him how? I asked.

Grandpa shakes his head, and his grip tightens. Don’t listen to him. He can only trap you.

His hands, and mine in them, tremble.

There is so much you didn’t tell us, I say.

Yes, he says. I had a purpose.

I WOKE WITH THE SHEETS TWISTED AROUND MY LEGS, MY FOREHEAD damp. The night floated in beneath the half-drawn shades, sulfurous streetlights and neon signs glowing in the windows of twenty-four-hour delis. The digital clock on my nightstand glared at me, an eternally open eye. Just past midnight.

I pulled on a sweatshirt and went out onto Amsterdam Avenue. The air was cool, gusts of it lifting my hair in the wakes of passing cars rushing down the hill. A few smokers lingered outside the bars. Taillights dashed the glass storefronts and disappeared in the heavy darkness around the cathedral. I crossed to the traffic island and sat on the lone bench. Moments later, he appeared, traveling slowly up the hill, dressed in the same winter coat and flat cap, shadowless in the night.

He sat beside me on the bench.

I wasn’t frightened this time—I couldn’t afford to be. Whether the old man’s mind truly drifted or he just liked to keep me off guard, I had to speak carefully if I was to learn anything from him.

“Hello again,” I said.

“Good evening.”

“Can’t sleep?” I asked. The old man was silent for an instant, and then sighed, a long, relaxed exhale, as if I wasn’t even there. I wanted to grab his lapels, stare straight into his pale eyes, but I couldn’t—he might vanish in a puff of smoke. Pretend you’ve been expecting him. Pretend you have all the time in the world.

“I can’t sleep either,” I offered.

“Bad sleepers,” he said. “It’s a curse. As much a curse as anything. Yes?”

“Yes,” I agreed.

“I can’t sleep,” he continued. “So here I am. Wandering at midnight.”

“Like one of the Penitents,” I suggested. My heartbeat sped up, waiting for his reply, waiting for him to acknowledge this strange thing that was happening at the edge of my understanding.

He nodded. “The angel is one of them too. One of us, the exiled. But I don’t pity him,” the old man said.

“The Angel of Losses?” I asked.

“Yes. Angels are half fire and half water,” he said. “But they look like you and me.” He eyed me. “Well, not like you.”

“He’s the guardian of the River of Stones,” I said.

“Is that what Eli told you?”

“No,” I said, and my voice was bitter. Grandpa had told me nothing. I confronted that fact again and again. In my work, I wrote abo

ut the repetition compulsion—reliving a traumatic event over and over, in reality or dreams or hallucinations. He told me nothing. He told me nothing. He told me nothing.

“He was cast out,” the old man said. “The angel cannot cross that river any more than you or I can.”

“Why not? What did he do?”

He scratched at his left shoulder absently, and his attention drifted away. I felt a small twitch of fear, the same as in my dreams of Grandpa, the anxiety of time running out before all had been said that needed to be said.

“I’ve been dreaming of Eli,” I told him.

“A dream uninterpreted is like a letter unread,” he replied. His voice was low and rich. Certain and unhurried. “Do you know who said that?” He paused but I had no answer.

“Waiting, waiting, waiting,” he sang, waving his hand before him. “I’ve kept the angel waiting so long.”

“Waiting for what?” I whispered. I was afraid.

“For another chance,” he said. “Another chance to go home.” He paused. “You’ve heard him calling, then? Calling for his people to rise?”

The angel on Simon’s map was a metaphor, a fairy tale, but the old man’s angel was here, speaking, if only I’d listen. “I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t think so.”

The old man put his hand on my knee, and I was surprised by its warmth and weight. He was no figment, no ghost, either. “None of us can help him. No one can. Remember that.”

He stood and surveyed the red-glowing cars sailing down the hill. I wanted to ask him why Grandpa was coming to me in my dreams, and why the old man was coming to me in their aftermath; why Holly was painting faceless men in a maddening paradise; why Nathan was afraid of our books.

But before I could speak, he did: “The necklace. Remember, you’re just holding it. For Eli.”

“Eli’s gone,” I said.

“Eli,” he answered, “will be here soon.”

Five

Holly went into labor three weeks early. The baby was small but healthy. He lay splayed out in a fiberglass crib, a fierce pink color, dwarfed by his diaper and hat. His eyes were a striking blue, pale but electric, like the morning sky caught in glass. She had a boy, just like Grandpa had told me in my dream. And just like the old man had predicted, they named him Eli.

If I felt any ache at the sight of the baby—any tug deep inside me—I pushed it away. He would grow up to be like Nathan. I didn’t want to love another person just to lose him to that man.

After a few days everyone came home from the hospital. Cars lined the block and crammed the driveway. My parents and I stood in the foyer for a moment, collecting ourselves. My father was stoic. My mother blinked repeatedly. Nathan’s sister-in-law Yael appeared to greet us. “Chava’s resting upstairs,” she said.

Holly was in bed, alone, so pale her lips seemed powdered white. It was still warm outside, barely autumn, but the blankets were piled on top of her, and she looked like a child.

I sat at the edge of her bed. “How are you feeling?”

“I hurt,” she said. No brave grin.

“I guess I shouldn’t ask what hurts,” I joked. She didn’t smile.

“Sorry,” she said. “I’m so tired.”

“Don’t apologize, Holl,” Mom said.

“Can you bring him back?”

“Let Nathan keep him for a few minutes. You have to get some rest.” Mom put her hand on my back, right over my nearly healed tattoo. I hadn’t told her about it yet. “Come on,” she said to me.

“I brought you something,” I said quickly, and reached into my pocket for the necklace.

“Oh, it’s one of those evil-eye charms,” Mom said, holding it up for Holly to see. The pendant spun slowly, winking blue circles.

Holly stared at it blankly for a moment and then pushed herself off the pillow. “Put it on,” she said. Mom fastened it around her neck, and Holly sank back down into the bed.

I thought about the old man’s insistence that it wasn’t a gift but something on loan from Eli. It didn’t make sense to give, or return, a charm necklace to a newborn, but still, when the clasp shut against Holly’s skin, I felt like I had made a mistake.

“Thanks,” she said. She had closed her eyes. Then, “Mom, can you bring me some ice?”

Mom kissed her forehead and gestured for me to follow her out the door, but I stayed, sitting on the bed with Holly. Just the two of us.

“Do you love him more than anything in the world?” I asked, ashamed that I only knew how to speak about such things in clichés.

But she considered my question, her brow furrowed. “It’s different than anything else,” she said. “When he cries . . . I feel it. I feel itchy. Like I’m trapped in my body and I have to get out. To him.” She looked me in the eyes, and for an instant I felt the sensation she had just described: unsettled from deep within.

“Do I sound crazy?” she asked, a half smile on her face.

“No.”

“Don’t tell anyone.”

Her plea cut through the chill that usually made our words clumsy and numb. “I won’t,” I said. “I promise.”

Heavy footsteps sounded down the hall. Nathan pushed into the room, bringing our moment to an end. He kneeled bedside in front of Holly, ignoring me completely. He radiated tension, but he laid a hand on Holly’s cheek so gently. His nails were bitten, his cuticles inflamed.

“Where is he?” she mumbled.

“Sleeping,” Nathan said. “Get some rest.” His voice was low, its natural authority muted—not bossy but reassuring—and Holly closed her eyes.

Neither acknowledged me as I stood up to leave the room. I paused in the doorway. The day had finally quit, just an orange glow around the curtains. Nathan was murmuring softly, his forehead against Holly’s, his eyes closed too.

I found my father in the backyard. “It’s like I’m an intruder in my own house,” he said.

“To be fair,” I said, “you did give them the house.” If my mother and I made a game of calling each other to worry about Holly, my father and I had a different habit: taking turns being alternately forgiving of and spiteful about Nathan’s family. He didn’t respond.

“She doesn’t seem well,” I said.

“She’s exhausted.”

“I know. That’s not what I mean.” My father stayed silent, concentrating on the horizon. “She doesn’t seem happy,” I continued. And hadn’t I wished this on her a thousand times? To realize she was unhappy with her choices, as I believed any sane person in her position must?

Nathan’s relatives moved behind the bright windows of our house like characters on a sitcom, telegraphing their ease with one another. And here we were, lurking at the edge of the light seeping from their tableaux, literally outside the home that had once been ours.

THE NIGHT BEFORE ELI’S CIRCUMCISION, THE HOUSE WAS spotless—the carpets smelled fresh; the furniture was at right angles; the old table by the front door was bare of mail and shining as if freshly polished. “It’s your dad,” Yael explained when I arrived. My mom had insisted I stay over the night before to help prepare for the sixty guests and to save them the chore of picking me up from the train in the morning.

“I think he’s going stir-crazy,” Yael continued. She usually wore a wig, but now I could see her hair was blond and cropped in a pixie cut. From the neck up, she looked almost trendy. “If he’s not on his phone in the backyard, he’s vacuuming.”

I came into the kitchen to find Mom rushing around, while Holly slouched at the table, her chin in her hand. “Not that cabinet,” Holly said sharply, and I was surprised she could summon the verve; her complexion was so sallow, her eyes so tired. “Those are the dairy plates, remember?” My mother sighed—it was the sigh she gave when she was restraining herself.

I backed into the adjoining living room and found Eli nestled inside a carrier, pale fabric piled up to his chest. His little eyes were soft pouches, slit with that bright, impossible blue, his tissue-thin skin dark with the

veins beneath, only the faintest wisps of hair on his head. He waved his arms around, his tiny fingers curled into his palms.

“Would you like to hold him?” Nathan asked. I jumped. He was standing right behind me.

“Yes,” I said.

“Wash your hands first,” Holly called.

I returned to the kitchen, where Holly and my mom were still banging dishes wordlessly, and did as she asked. Nathan was holding the baby now, one hand beneath his back, another beneath his head, his little legs against Nathan’s chest. Nathan smiled down at him, maneuvering through the room as if the baby were a compass or divining rod. Nathan seemed totally comfortable, exuding none of Holly’s edginess. He lowered Eli into my arms expertly—Nathan’s sleeve didn’t even brush mine.

The baby’s head lolled in the crook of my elbow, his body resting in my lap. Eli was impossibly light, lighter than a textbook. He made slight mewling sounds, his wrinkly lips opening and closing over his gums. “Be careful of his belly button,” Nathan said, sitting beside me. “It hasn’t fallen off yet.” I had never seen him like this—relaxed, warm. The aura of bad humor that always encircled him like a cloud, charged and about to burst, was gone. “Eli, this is your aunt.” He touched the baby’s chest. “Say hi. Say hi.” Eli waved his fists, each the size of a chestnut. I was silent, but for once I wasn’t biting my tongue. I didn’t know what I thought. I didn’t know what to say.

“By the way,” Nathan said. “How did you find the amulet?”

I opened my palm to the baby, and he tapped his hands against mine, no more than the weight of a kitten’s tail. “What amulet?”

“The one you brought for Chava. It’s too bad she went into labor before you could give it to her.”

I was studying the tracery of capillaries on Eli’s cheeks. His skin was so delicate. I remembered that he needed another month or so inside. He was too fragile to be out here in this world. And his eyes. I had never seen such brilliantly blue eyes.

“I’m sorry, what were you saying?” I asked.

“The protection amulet. For a mother giving birth. The one you gave to Chava.”

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses