- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

The Angel of Losses Page 5

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 5

“It’s your name on the slip.”

“Yes, but I didn’t order it. It’s a mistake.”

She shrugged. “Okay. Leave it on the counter.”

I looked at the flimsy receipt tucked into the book. My name, Marjorie Burke, and my student ID number. Sent from the University of Texas at El Paso. “Wait,” I said. “I’ll take it.”

I tucked the book under my arm and went to find an available computer outside the stacks. I checked the Library of Congress database; there were only three copies of the book in all of North America, and two—one at Arizona, another at UCLA—were missing. I logged in to my library account. It registered an order for the book on August 14, a little over a week ago and days after I had finished my preliminary research and returned the last of the sixty-seven books I had ordered from collections across the country. Next to the entry was the code ADMIN 8141573.

I scribbled down the serial number and returned to the loan office. The girl behind the counter stared at me. “I found this code in my account,” I said, sliding the paper toward her.

“I’m going to get my supervisor,” she said, relieved, and disappeared into a back office.

A few minutes later a man appeared. He was tall, with narrow black glasses and brown hair falling over his forehead. “Can I help you?” he asked. He had the same bored affect as the girl and was dressed unseasonably in a baggy green sweater, protection from the library’s air-conditioning.

“Yes, I want to know what this code means. This book came in for me, but I never ordered it.”

He tapped the paper. “That’s me. I put in the order for you.”

“What?”

He pushed his overgrown hair behind his ear, blinked a couple of times.

“And why did you do that?” I asked.

“Well, I saw you were ordering every book in the database linked to the Wandering Jew. Juan Espera en Dios is a Spanish incarnation—”

“I know who Juan Espera en Dios is,” I interrupted. “But I don’t do the Americas.”

“What exactly is your research on?” he asked.

It had been a while since someone asked me to describe my dissertation—a while since I’d been to a dinner party or university reception or bar—but I had an old strategy. If I doubted the sincerity of the speaker’s interest, or was just feeling difficult, I gave them theory: uncanny doubles, split subjects, the subversive feminine sublime. The listener’s eyes would squint, indicating concentration; then they would relax back into blankness. He or she would offer a quick nod, feigned comprehension, a signal to move on to a new topic. If I liked the person, or was a little drunk and expansive, I went straight to the story: blood-soaked ghosts, wandering exorcists, flesh burning with illegible magic. I was always a little surprised when that didn’t win them over—usually it didn’t. You would think everyone could appreciate a good ghost story.

The librarian was tall but not too tall, with cheekbones just subtle enough and lips just thin enough to save him from being pretty, and his eyes were just squinty enough from screen time to hide their brightness.

And yet I still gave him the first answer.

“Feminist postmodern psychoanalytic critique of exorcism in the British Gothic tradition.”

“Oh.”

“Yeah.”

“Well. You were ordering so many—”

“Why are you following my book orders, anyway?” I had been feeding search criteria and requests into an electronic processing system, never a thought about the person on the other end. It was like he had been reading my thoughts. I didn’t like that, no matter how nice he looked—actually, that made it worse.

“It’s been a slow summer,” he started. “Look, I’m sorry if—I thought it might be helpful. The book is kind of hidden. I was researching for months before I came across it.”

Of course, I knew the Wandering Jew had found other scholars—I had read thousands of their pages—but here, at this university, it had just been me and the immortal. I never considered that while I combed through the pages of Enlightenment Europe in the narrow halls above, someone was in the basement, conducting the same search through rambling American apocrypha.

“Researching what?”

“The Human Geography Project, with the Anthro Department, and Near East Studies. A digital map of folklore migration. The Wandering Jew. Other stuff too. I’m doing another degree in information science. This—” He gestured to the empty loan office, the buzzing air conditioner, the sullen girl reading a book, her feet on the counter. “Day job.”

“Okay, thanks for the book,” I said quickly. “I don’t do the Americas. And I do my own research. So. If you see my name. You know. Ignore it.”

He exhaled. “Sure. Sorry, Marjorie.”

Suddenly I wanted to backtrack. I could tell him about the story. He would find it interesting, my Wandering Jew, with magic written into his skin. I could tell him my family never asked about my research, confess that I was too possessive to discuss my work with the other students in the literature program, and that I had no one to talk to about the tale around which my whole life turned. I had a rough morning, I could say. I’ve been working so hard. I haven’t been sleeping well. The White Magician was a rebbe, and Grandpa had never told me.

“I’ll take the book,” I said, by way of apology. He just shrugged.

I opened it in the nearby reading room. Whether the text proved relevant or not—and I was sure it would be the latter—the book itself was a comfort: a return to my work, quiet study rooms and surprises that were only scholarly in nature.

The chief Rabbi of Monterrey suggested the mysterious stranger was Joseph Della Reina, the medieval rabbi who could no longer bear the suffering of his people’s exile, and was thus determined to force the coming of the Messiah.

One of Della Reina’s disciples died, one went mad, and one gave himself to apostasy. The rabbi himself went into a new kind of exile, fated to be born again and again, generations of penitence, until he might redeem himself, just himself, and not all of mankind. Meanwhile, the Messiah remained lost in a great desert beyond a river of stones.

But this stranger, it was agreed by the townspeople, was not the mad rabbi, but a different immortal Jew.

I shut the book. Had I picked it up the day before, I would have read and dismissed the story without a second thought—it was folklore, nothing at all to do with my research—but today was different. This was the same story depicted in Holly’s painting: the condemned men hanging in a swirling sky. It reminded me of Grandpa’s Manasseh too, a holy man overcome with sorrow for his people’s spiritual exile.

The story had come to me now three times in a single day. Holly would call it synchronicity—the old Holly would have, anyway. She had spent her twelfth year presiding over a Ouija board, her fourteenth reading tarot, her sixteenth writing down every dream in an attempt to uncover her past lives. The summer before the start of her sophomore year of college she announced her intention to convert. We were drinking in the backyard, beer for me and juice for her, ants crawling over our bare legs and the low sky a deep polluted orange. She hadn’t told me about Nathan yet—I didn’t realize how serious it all was—and I laughed. “When did you start believing in God?”

She was silent for a moment, and when she spoke her voice quavered. “Marjorie, I’ve always believed in God. Didn’t you know that?” She stared at me through her tears, with an expression of such betrayal it left me dumb, too shocked and sorry and confused to respond.

We didn’t talk about it again. I went back to school, to ruin ghost stories with jargon about social contracts, patrilineage, and national anxiety.

To me, the mad rabbi was just a coincidence. I wasn’t a believer.

And yet.

I RAN ALL OF THE ERRANDS I HAD BEEN IGNORING. I CHECKED my mailbox, did my laundry, downloaded several fellowship applications, so I wouldn’t have to teach next year either, however impoverished it would leave me. I moved my bed and vacuumed under it.

I called my mother to tell her about my morning with Holly and Nathan, but she didn’t pick up and I didn’t leave a message. What would I say? Holly was painting a picture of doomed, white-eyed rabbis. She let me feel the baby move. Grandpa wrote a story about a magic rabbi, and I don’t know what it means, where it came from, why he would change his fairy tales into a religious story—or if he had changed religion into a fairy tale—when he had never spoken about religion at all, certainly not Judaism, except to make bigoted remarks about the families clustered around the Berukhim Yeshiva.

I read the marbled composition book again and felt no closer to understanding its mystery. There were four titles listed at the beginning, three missing stories in I didn’t know how many notebooks. Gone. I remembered Grandpa’s friend Sam, nervously delivering the books, and Dad, driving off and letting me think he had destroyed them. Had they read this story?

I sat on my bed for a long time, the notebook with the strange sketch inside pressed between my folded arms and my heart, studying my grandfather’s watercolor, framed beside the door. It was a seascape, a turquoise ocean with curling traces of white foam. The sky above it was washed out, ivory fading into orange at the horizon, a glowing equator thin as a pen stroke. A flock of black birds, slack check marks, hung in the top left quadrant. They seemed unmoored like the men in Holly’s painting, neither receding into the sky nor swooping down from it. I focused on the swirling currents, white and blue and purple and black twisting around one another until they took shape—a hand, a flowering vine, a dissolving eye. I blinked and the brushstrokes relaxed back into pretty nothingness, but it was too late. Grandpa’s whole exercise in painting now appeared deliberately obscure instead of pleasantly vague.

It was early yet, only ten o’clock, but I had barely slept the night before, and I knew I needed rest so I could concentrate on my work. I turned off the lights, climbed into bed, and stared at the streetlight glow clinging to the ceiling. I stared at the door, outlined in black, the hall beyond quiet, empty. I stared at Grandpa’s notebook, a sliver of darkness on my desk.

At midnight I turned on the light and opened the book again. As the story went on, his handwriting grew smaller, tighter, darker. There was an urgency in the script, or maybe something else—anger or fear. I thought again of my grandfather at the end of his life. A disordered, angry twin of the man who painted oceans and told tales of a kind magician who never failed. I took a legal pad, determined to expel the words cycloning in my mind and cage them behind a set of ruled lines. The White Rebbe. The Sabbath Light. The Angel of Losses. The River of Stones. The Penitent. The Wanderer.

I copied the sketch from the inside cover of Grandpa’s notebook, its many arms, its meticulous angles, and then I copied it again, seeing this time the subtle swelling and tapering of the lines, the elegance of it, and then copied it again, and copied it a fourth time, because it was really so simple, deceptively simple, fundamental, pure.

It was one o’clock. I called a friend from my old writing group.

“Insomnia,” I said. “Again.”

“Just your luck,” he said. “I’m leaving Brooklyn now. We can meet downtown.”

An hour later I arrived at Warsaw, a Polish dive serving cheap well drinks and pierogies under a canopy of Christmas lights. The tables were filled, chairs crowding the aisle, but I didn’t recognize any of the customers. I took a seat at the bar. The blond bartender was intent on the elderly man beside me. He wore a brown plaid hat, round on top with a stiff bill shading his eyes, a fringe of white curls at the brim. He leaned over his mug of tea, shouting a joke to her in what must have been Polish. She laughed, and he leaned back a bit, content.

I ordered vodka, put the anemic lime on a napkin, and swallowed half of the drink. I was itchy and nervous with fatigue. Next would come the headaches, then the flashes in my peripheral vision, like an alarm heralding collapse. I finished my drink.

“Careful, careful,” the old man said. He had a slight accent. “We must remember our sorrows, not drown them.”

“What did you say?” I asked. He was familiar: the wide mouth, the silver stubble, the bright blue eyes, watery and set deep in his flesh. His voice too—the tenor, the authority.

He removed something from his pocket. A silver thread fell from between his pinched thumb and forefinger. “Here,” he said, and I leaned in to see the pendant tracing watery rings on the bar. It was blue and just the size of a chickpea, but it possessed a disproportionate depth, layers of tinted glass, the surface textured with an opalescent fingerprint.

“For you,” he said, and held it out to me.

“Oh, no thank you,” I said. “I couldn’t.”

“Don’t worry, not to keep,” he said. “To hold for a while.”

I knew him. He had tried to comfort me after Grandpa’s funeral, appearing by my side as I stood alone beside the coffin, suspended above the plot. I was the last mourner, and I knew that once I walked away, the workers waiting under the trees would lower him into the pit, the dirt wet and obscene. Grandpa would be gone forever, and the delicate forces containing my grief would weaken and I would spill across the earth. “Eli had a good life,” the old man had said. “Far better than he could have expected.”

I had been angry at this but unable to protest. I realized how little I knew about Grandpa’s life before us.

“Are you a friend from Brooklyn?” I had asked. The senior center had chartered a van. Sam had been too ill to come, and I didn’t think Grandpa had counted any of the other men as true friends; they were just neighbors who didn’t want their own funerals to be unattended.

“From before,” he answered. “I did him a favor once, when he was a very young man.”

The old man had produced a small, hardback book. The cover was black and pebbled with a silver word impressed on the back, and on the inside, faint Cyrillic handwriting filled the flyleaf. The pages broke in my hands like stale bread. We scattered the shards in the open grave, and something unlocked inside my chest—I hadn’t realized how constricted my breathing had become—and for a moment, I was grateful to him.

I wanted to ask him more: When did they know each other? And where? And what had Grandpa been like? And why are you the first friend from his youth I’ve heard of?

But before I could speak, the old man grabbed my wrist with freezing fingers. “It’s a lie,” he said. “Whatever he told you. Everything he told you. A lie.”

I broke away from him, rejoined the small crowd by the parked cars—a few of my parents’ friends, the small band of old men from Brooklyn—and when I looked again, the old man was gone.

Until now. “Do you remember me?” I asked.

The old man laughed, and my throat tightened. He sounded like Grandpa. He had the same blue eyes. He gestured to the necklace. “Go ahead,” he urged. “It’s good luck.”

I didn’t want to insult him, not before I could learn who he was; or maybe it was just that he sounded so much like my grandfather. I put on the necklace. It was clammy from the messy bar, chill against my chest.

“I remember everything,” the old man said.

Immediately, I thought of The White Rebbe and the Sabbath Light. Grandpa had kept the story secret; he’d intended for the notebooks to be destroyed. He wouldn’t want me talking about them. Yet this friend, who sat beside me now, gazing into his empty glass, his mouth moving silently—he had been a secret too. I felt my loyalty to Grandpa’s wishes waver.

“You asked me what Grandpa—Eli—told me. You said it was a lie. Did you mean . . . did you mean the White Rebbe?”

The old man scrutinized me. I held my back straight, my gaze steady. There was no reason to fear him. Maybe I feared what he would say.

“So he did tell you.” The corner of his mouth twitched—the beginning of a grin, or a frown, I couldn’t tell. “He said he would take it to his grave.”

A hand fell on my shoulder. My friend, already heading to the door. “Meet me outside.”

I turned back to t

he old man.

“Go,” he said. “Don’t worry. We have plenty of time.”

I didn’t want to leave him there, give him the chance to disappear again, and with him any answers he had about Grandpa, his story, his secrets. But he was waving his hand toward the door, and his promise felt as solid as the necklace he had given me. I slid off the stool. “Be right back.”

Outside, I gave my friend the last of the money I had scrounged up that morning in exchange for a folded paper bag.

“We’re going to Eighth Street instead,” he said. “You want to come?”

“No. I’m going to finish my drink. And I have work to do tomorrow morning.”

“I haven’t seen you in months. Since you quit the writing group, I think.”

“Well,” I began. “Deadlines.” We were all under tremendous pressure to produce, to overachieve, and we must have all liked it, or we would have dropped out by now. But I wondered if I took it too far. I wanted to decide what the story meant. I wanted to decide what mattered and what didn’t.

But he was already looking beyond me, waving to a man and a woman crossing the street toward us. “Eighth Street!” he shouted. “I just texted you!”

I studied the sidewalk while they exchanged a flurry of names—who was waiting inside, who was still on the train, who was unaccounted for—and decided to have one more round. I glimpsed the old man, still at the bar, as the door began to swing shut.

Before I could follow them inside, the other man spoke. “So, did you read the book?” he asked.

I looked up. He wasn’t wearing his glasses, and his lashes were long and black, his eyes bright and gray like tin. “Juan Espera en Dios,” I said.

He laughed. “It’s Simon, actually.” He offered me his hand, and I took it. “Nice to meet you. Officially.”

“Are you following me or something?” I asked. The question, I realized, was meant for the old man—his reappearance, coincident with the notebook’s, was uncanny—and only bubbled to the surface now. I voiced it with a shade too much urgency. I was shaken, maybe a little bit scared.

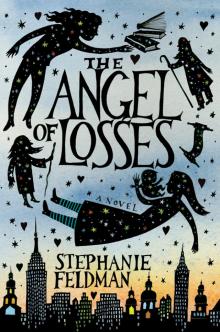

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses