- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

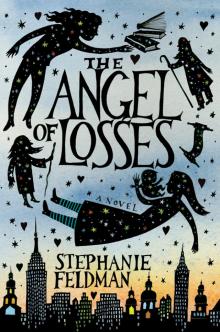

The Angel of Losses Page 19

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 19

We both lay awake until morning.

IN THE MORNING I CALLED MY MOM, WHO HAD RETURNED TO the hospital with Holly. It had been forty-eight hours since anyone had heard from Nathan; no one was answering the phone at the house, and he hadn’t appeared on any family doorsteps. Mom told Holly he was resting, that Simon and I were driving out to pick him up, and Holly had accepted her lies without comment. “She’s just so focused on the baby,” she whispered, but I wondered if Nathan had prepared her, somehow, for his disappearance.

I had only one lead: the yeshiva, which was mysterious even to his family. But first we stopped at the house, pulling into the driveway—right behind Nathan and Holly’s beat-up station wagon.

“Well, that was easy,” Simon said.

“You’re assuming he’s where his car is,” I answered.

“What are you going to say to him?”

“Everything.” I was furious with Nathan, for his apparent abandonment of Holly, but also for embarking on this—whatever, exactly, this would turn out to be—without me.

“Great,” he said. “This should go well.”

The front door was locked, but I still had my keys. We went inside and stood in the dark foyer, listening. I opened the door again and slammed it. Simon jumped, but the rest of the house was silent.

“I’ll look upstairs,” I said. “You look downstairs.”

“But who will guard the door?”

I shot him a look. “Is this funny?”

“No,” he said. “This is the opposite of funny. What am I supposed to say if I find him?”

“Are you afraid of him?”

“Not as afraid as I am of you.”

“So why aren’t you downstairs yet?”

We parted. In Eli’s room, the crib looked like an altar. Pages of Hebrew text were scattered on the mattress and stuffed beneath it. The mobile was thick with blue yarn, strung through more slips of paper with black scrawls. If the necklace was there, it was deep inside the psychotic weave, invisible. I left and closed the door behind me.

The first floor was empty, and so I went to look for Simon in the basement. “Hey,” I said, coming down the steps. “Is there a way to disable the station wagon? Not permanently, but so if he shows up again, he doesn’t have a getaway? Hello?” Simon was standing in the middle of the room; all around him, sheets of paper moved in the slight draft as if they were alive.

I had to grasp the railing. I took each step carefully and knelt on the concrete floor. The pages were ragged along one edge, torn from some binding, and scrawled with hasty black strokes. There were multipointed stars, multidimensional cubes, multiarmed trees, multipointed compasses. Some lines dissipated at the edges, the swift stroke of a marker; others were studded with holes where a ballpoint bit through the paper. Nathan had been desperately trying to re-create the Sabbath Light, the same symbol I had been unable to draw myself, but whereas my tattoo was a whim, his work was purposeful; he had invoked the Angel of Losses to protect his son.

Simon was on the floor now too, collecting pages. “There are hundreds of them,” he said. He sat back, squinting at one drawing, and I snatched it out of his hand. It wasn’t his to examine.

“You know what this is,” he guessed. I didn’t know if he recognized the similarity to my tattoo or if he was responding to the territorial way I had taken the paper from him. I didn’t answer.

Inside the car, Simon stared straight ahead. “What are you thinking?”

I had to tell him something—so I explained what had happened the night before the circumcision. Eli exposed to the cold night air. Holly insisting I never speak to Nathan again. Nathan, with dirt on his face. Me, screaming like a madwoman.

“I know how it sounds,” I said. “But I feel responsible for Eli being sick.”

“You know you’re not,” he assured me. “This is one of those things that’s out of our control.”

I said nothing; I let him think I agreed.

We parked across the street from the Berukhim Yeshiva, an orange brick cube and small parking lot settled between a dentist’s office and an accountant’s. Two bearded men with rainbow fringe at their belts stood talking on the lip of pavement along the front of the building. Since they took over the lease, the Penitents had been a mild curiosity in the town, like the Jehovah’s Witness hall or the Masonic Lodge, different but not distressing—but their presence tortured Grandpa. Did he interpret it as a signal from Solomon? I didn’t know what kind of quotidian magic would send the Fellowship here—clipping real estate listings, or whispering “New Jersey” in the Penitents’ dreams.

But there was a hand in it. Maybe Solomon had even diverted Nathan’s path, sending him to the Berukhim Fellowship, and then to Holly too.

Or there was a force greater than the old man—not a heavenly king or divine watchmaker, but the dumb and unstoppable motion that carried the glitch in Grandpa’s DNA through Holly and into her baby, a history that needed no man to write or speak or remember.

A maroon minivan pulled into the lot. I sat up straight, watched it park and expel another black-hatted man. He paused halfway across the parking lot and answered his cell phone, then turned around, drifting back toward the car with the phone at his ear. He stood with his hand on the door, talking for a moment, and then climbed back inside the van. The taillights went on and the car reversed.

“That’s Nathan’s friend,” I said. He had been part of the ceremony I interrupted, one of the three Penitents who stood with dirt on his hands and face, watching silently as I shouted at Nathan. “Follow him.” He passed the high school and turned down a tangle of lanes set with identical twin homes with tan siding, a yard where a group of boys in dress shirts chased one another, shouting cheerfully in Yiddish.

Grandpa, with his perfect American accent, would have understood them.

The minivan pulled up to the curb in the middle of the block, and the driver ran to the door.

“Now what?”

I unsnapped my seat belt. “I’m going in.”

“Okay, Rambo, maybe you should calm down first.”

“I’m calm.” I glared at him. “You know, I really hate that.”

“What?”

“When men tell me to calm down when I’m perfectly calm. I can be calm and angry at the same time.” But I wasn’t angry—I was guilty, for stopping Nathan’s ritual, for failing to uncover Grandpa’s secret sooner, for letting Nathan disappear. I was frightened too, that something terrible would happen to him. That would be my fault as well.

Nathan’s friend was returning to the car, a paper bag in his hand. I jumped out of the passenger seat and ran across the empty street. “Hey!” I shouted. The man stopped halfway down the walk, his eyes wide. “Where is he?” I demanded. The man looked at me, and then beyond me—Simon was crossing the street to join us. “Hey!” I clapped my hands twice in the space between us. “I’m asking you a question.”

The children in the neighbor’s yard stopped their game, instinctively moving closer to one another, watching me. One ran into the house.

“Who?” the man mumbled, not meeting my eyes.

“You know who—”

“I’m sorry,” Simon interrupted, laying a hand on my shoulder. “We were just, uh, driving by, and Marjorie thought she recognized you—you’re a friend of Nathan’s?”

The front door opened, and a young woman with a toddler on her hip came to the threshold. “Aaron?” she called, and took a tentative step outside. Another toddler—a girl—followed, her hands on her mother’s skirt. Suddenly my voice was gone. I wanted to shout at the woman, Come with me! Get all of your children and I’ll help you leave. I’ll help you start again. But why should I think that? They looked happy—a happy family.

“It’s okay,” the man said, speaking softly to his wife, and then continued in Yiddish. She listened to him, and then she and her daughters looked at me—she wore a new, sad expression, the children a blankly curious one. And then she closed them back inside the h

ouse.

“He came here a couple of nights ago,” Aaron said to Simon. He squeezed his fist around the grease-stained bag. There was nothing sinister about the phone call in the yeshiva parking lot—he had forgotten his dinner at home. “He said he had found the rebbe’s library. Most of it. One book was still missing.” He shook his head. “But it’s impossible. It was destroyed in the war—if it ever existed at all.”

I nudged Simon, indicating that he should press him, when Aaron continued.

“You’re the one with the map, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” I said. “He is.”

“The map,” Aaron repeated, taking a step toward us, his eyes fixed on Simon. “With Akiba.” Aaron looked at me. “Nathan thinks he’s Akiba, but he’s Ben Zoma.”

WE DROVE BACK TO THE CITY. I WATCHED THE HOUSES SLIDE BY, like the earth was coming apart one layer at a time and would soon release us to spin in the atmosphere. Like Rabbi Akiba in Holly’s painting.

We sat in silence until we got to the bridge, backed up as usual, and when traffic halted us over the river, Simon said, “Rabbi Akiba traveled the Middle East on behalf of a Hebrew general who revolted against the Roman Empire. That’s how he made it onto the map. Akiba thought the general was the Messiah.” He paused. “There’s a legend that Akiba took three disciples in search of paradise, but of course it was impossible for them to cross over.”

“Right,” I said. “One dies, one becomes an apostate, and one goes mad.”

“Ben Zoma is the last one.”

Aaron was wrong. Nathan knew he was no Akiba; he knew he would pay a price. That’s why he had told me that Holly would need me. He had found the final notebook, The White Rebbe and the Angel of Losses; he knew exactly what the price would be and had already—perhaps—arranged to pay it. It was too late.

SO I THOUGHT. BUT AT THE HOSPITAL NOTHING HAD CHANGED. The test results had come back inconclusive. Lab error. They had to draw blood again, and Eli, exhausted, didn’t even whimper when the needle punctured his skin. Holly had erupted in all the tears her baby was too weak to cry. She was in the PICU with him when I arrived, draped in blue paper, her scrubbed fingers on the glass between them.

My mother had been calling doctors and hospitals in Florida. She wanted to transfer Eli. “I want to be able to help Holly,” she said.

“So why don’t you come back here?” I asked, but she didn’t have to answer. She had always been the most accepting of Holly’s new life, however difficult an adjustment it was; but now, with Nathan’s disappearance, she was done. She wanted to get Holly and Eli as far away from his family as possible.

“He’s coming back,” I said. It had only been three days since Eli was rushed to the hospital, but time had dilated, strung out on the pull of his seizure, as irresistible as a black hole. Nathan’s absence was stretching toward eternal. Unforgivable. I remembered how angry I had been at Holly for taking the house, how I had thought of her pregnancy as a cheap shot, a petty victory over me. As if her choices had ever been about me.

“Oh, Marjorie,” my mother said. “It’s over.”

SHE WAS RIGHT. I DIDN’T KNOW WHERE NATHAN WAS. I DIDN’T know how to find The White Rebbe and the Angel of Losses, which might explain what Nathan was planning and how to find him, and I didn’t trust the old man to tell me himself what the angel’s price was. I didn’t even know how to summon him. I was at his mercy. I always had been.

But then I received a message from Simon.

Sometime overnight, Nathan had added himself to the map.

THE MAP WAS GROWING DAILY—MORE BIOGRAPHIES, MORE HISTORIES, more ethnographies, more folklore—a sea of multicolored markers. I opened Nathan and Simon’s experimental layer, the Berukhim legends hinting at the location of the River of Stones. Nathan meant to solve the problem of graphing what didn’t physically exist; to chart a hundred distorted tellings, and then triangulate the path to the place they described, the edge of this world, the end of it. But Nathan couldn’t be hunting for a secret road in Asia. He was hunting for an access point to the angel’s magic, the light that illuminated paradise and burned in Solomon’s skin.

The rash of blue icons dotted nearly every continent but were thick over New York and its suburbs: the Brooklyn apartment where Holly and Nathan lived briefly after the wedding; his parents’ home and the school where Holly studied for her conversion; the dormitory where they met and the temple where they were married. The hospital where Eli was born, and where he was treated after he first fell ill. The hospital in Manhattan where he now slept amid the shudder of machinery. The Berukhim Yeshiva and my parents’ house. My university. My university library. My apartment.

Upstate New York: Nathan has only a few memories of his father, mostly the stories the older man told. The one he remembers most clearly is about a man who apprenticed his young son to a trio of dead rabbis. The boy joined them in a classroom deep in the cemetery earth, and they taught him to speak the languages of animals. Nathan grew up admiring the parents’ piety in relinquishing their son to the great sages. Is God the greatest father? Should we sacrifice our children to His glory? Is that what his father intended to teach him? Was he trying to teach him anything at all?

Mizoram, Northeast India: They translated, from the native dialect to Hindi to English, three traditional mourning songs that recount the tribe’s travels in search of a home, their time spent hiding in caves from hostile kingdoms, and how when they arrived here they saw words written in the trees, entreating them to settle. This was proof, Nathan thought: There is more to the world than even the faithful dare to believe, and his family is wrong about him, and his own instincts are sound. But, like always, the moment of vindication burned so brightly, it was soon extinguished, and again he felt doubt, and fear, and the need to search on.

Safed, Israel: Six hundred years after the great sages died, Nathan, having sensed a great chasm beyond the rituals and laws his family built as a bulwark against time, traveled across the world to pray at the graves of Karo, Luria, Cordovero, and Alkabetz. For the first time, he rose at midnight to lament with the Berukhim Penitents, and when he blinked dust into his eyes, in tribute to the Messiah, lost in a great sandstorm, the grit in his flesh felt more real than most of his life had, and he threw more dirt in his face, more, he was hungry for more. For three days he ate nothing and drank little, and he sat by the tomb of the first Berukhim Rebbe, meditating for hours, inviting the great sage’s soul to join with his own and reveal his mystical knowledge—but he never did come.

I thought it was my own failing. I wasn’t holy enough. I wasn’t ready. Now I know: He wasn’t there at all.

Williamsburg, Brooklyn: His stepbrothers were drunk already, the reception hall littered with crushed plastic cups, and his cousins kept clapping him on the shoulder, the congratulations, the confessions of relief, and every smack and footfall and laugh echoed in the space that always encircled and separated him. The canopy was erected on the plateau halfway up the cement stairs, and the air was thick with lights and car horns from the rush-hour highway. When she joined me, everything around us, everything that came before, and even everything that will come after, fell away. I wore a brilliant white robe that will one day be my burial shroud, a garment of protection, not because of the knots or names sewn into it, but because of something that came from our love. The sun set on all of the guests, and the city too, and we were alone under a prehistoric sky of stars.

New Jersey: It rains for three days straight. The yard is spongy and the sky is like stone. I wait for the rain to pause to walk home from the yeshiva, and even so, my face and hands are damp by the time I reach the front door. On the third night I’m woken by thunder so loud and immediate that for an instant I think a tree branch has fallen on the roof above. Then the windows flash white and I realize it’s the storm. Somehow Chava sleeps through it, and I’m relieved. She’s seven months along and too uncomfortable to sleep most nights.

I go downstairs for a drink. In the unlit kitchen, t

he water in my tumbler is gray and bubbly. It makes me think of the sea, though it tastes clean.

“Are you ready to begin?” a voice asks. It’s so deep that I’m not sure I heard it or imagined it, but I’m startled all the same. There’s a figure sitting at the dining table, a book open in front of him. He has long hair, its ends lifting away from his shoulders, crackling with static. His skin is the same color as the water in my glass, and his eyes are as white as clouds.

I blink and the figure appears different: his hair in motion, a stream going down a hill, his skin bronze, blackened at his eyes and mouth, burning, his eyes purple, the sea flowing into the horizon at sunset.

Many of my classmates still see metaphors in our books, or think they describe a time that has passed. But nothing has ever passed. I believed and I prayed. I meditated by the tomb of the first Berukhim Rebbe, who commanded the angels, and now an angel has come to me.

“Yes,” I say. “I am ready.”

East Side, Manhattan: He looks just like me. We are the same. His brain builds itself by experience, the experience of listening to my voice and looking at my face. He looks straight into my eyes, and everything inside of him organizes itself according to my reflection. So it was I who did it, I thought—the misfiring in his brain anticipating the one in my own. I was certain I was having a stroke. My vision obscured by mist and the taste of smoke in my throat. I prayed for help—let me not abandon them, not now!—but it was the angel coming to me. It was him the whole time, half water and half fire, suffusing the great atrium, sealed in by night.

There were four notebooks. Marjorie found the first, and I found the third. Marjorie has the fourth too. The White Rebbe has given it to her. The second was lost to us, until I commanded Yode’a to retrieve it for me, just as the first Berukhim Rebbe commanded him so many generations ago. Nothing is lost to Yode’a, except the White Rebbe, who has concealed himself. (Though he is still here, close by, the angel is sure of it.)

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses