- Home

- Stephanie Feldman

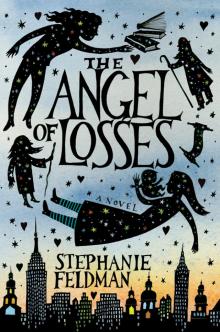

The Angel of Losses Page 17

The Angel of Losses Read online

Page 17

I will not leave you again, Eli assured him. Neither brother slept that night.

THE PRESIDENT OF THE ARTISTS’ ASSOCIATION ANNOUNCED that the Judenrat, the collaborationist ghetto leaders, had offered them employment passes to go into the city and work at the Jewish library, which was collecting all the books from the yeshivas and temples and museums of Vilna. The project was organized by a Rosenberg, but this Rosenberg was a German, a demon.

They’re going to make a monument to us after they’ve finished killing us, someone said.

We’ll smuggle the most precious books here into the ghetto, where we can protect them, the president said.

And where will we keep them? another asked. There’s no room here already for our bodies, even.

Eli always sat on the ground at these meetings, at the edge of the gathered circle, never speaking, so that no one could even be sure he was listening, but now he stood and walked into the center of the group. I know where you can hide them, he said. I live with my uncle in the alley behind Jatkow Street. He’s a scribe, and he has room to hide a million books.

The scribe on Jatkow? Do you mean old Solomon? But he must be dead and gone by now, someone interrupted.

He’s alive, Eli said. He’ll help you. If you give me a pass to work in the library.

Eli didn’t yet know what was coming. He didn’t yet know where he might go, or how he might get there. But the ghetto walls were impassible except for the pass. The pass was magic, and Eli wanted it.

That night, when midnight came, he heard his uncle’s footsteps beneath the floor where he slept, and then the cellar door creaking open. The old man came into the kitchen and approached its small window. Solomon pushed aside the heavy drapes and looked out at the ghetto.

Eli gathered his courage and came out from his bed beneath the table.

Do you smell that in the air? the old man asked. The moonlight turned his face to bone. Smoke, he said. The Angel of Losses is coming for me. He’s coming for the price I promised him long ago.

Uncle, Eli said. The Germans have decided to confiscate our books, and we’ve come up with a plan to save them. We must hide them in your cellar. It’s the only way.

He had rehearsed the speech and was pleased with the authority in his voice, the word we that initiated him into the association, the act of strategy and bravery that would initiate him into adulthood.

His uncle turned to face him, and Eli’s flush of confidence faded.

You are asking a favor of me.

Not me, Eli argued. Your people.

Solomon smiled then, but it was not a friendly smile. You, he repeated, extending his arm to point at his nephew. The light in the room shifted, a cloud passing over the moon, Eli thought. You are asking me a favor, and I will grant it to you. And when the time comes, he said, turning away again to stare into the night, you will do me a favor.

Yes, Eli said. The wind rushed against the windows, finding every crack in the walls, and he shivered. Yes, Eli said again. I will.

THE ARTISTS’ ASSOCIATION SET TO WORK. ELI RECEIVED a yellow pass to exit the ghetto every morning and return every evening. He walked across town to the Jewish library, a beautiful building that stood straight and tall and unhumbled outside the ghetto. At the curb, a large map of the world was on display, its continents faded and its wooden stand weathered. A fresh headline had been pasted at the top: GERMANY WILL LIVE AND THEREFORE GERMANY WILL WIN.

Some days there was a lot of work—like the day when a nearby temple’s Christian janitor reported that its library was being looted for heating material and toilet paper, and took Eli to his home, where his children played among the stacks of books he had hidden. The artists sorted books and hid the most valuable ones in their clothes and in the supply wagons that passed through the ghetto gates. They also argued about literature and politics in the vaulted reading room, or went into quiet corners to read the library’s holdings, or whispered about the increasing rumors of uncanny happenings inside the ghetto. A shooting star had been seen, the first piece of heaven dismantled, a portent. A suffering family had woken cured of their tuberculosis, a miracle. A baby had been born with a birthmark the shape of the Star of David. Some of the Hasids were rising at midnight, covering themselves in soot, and wailing in the streets, as if they could repent the ghetto away.

Eli followed the librarian, Weiskopf, around; he always treated the boy warmly and found him something to do. Maybe I could be a librarian, Eli thought. Eli liked the books—the feel of them, the weight of them. He liked that he was doing a good deed, and that he was admired for it. When the Socialists received a contract to bring furniture into the ghetto, they came by the library first, so the association could hide the volumes in cabinets, desks, and sleeping boards.

One day Weiskopf said to him, I remember your uncle from when I was a child. In fact, I think he wrote my parents’ wedding contract. Solomon was ancient even then, and I assumed he had passed. But you know, when they told me who had found a hiding place for these books, I wasn’t surprised.

The men from the association helped bring the books to the house. They stood in the small room, their eyes crawling the walls and corners, but left quickly, less curious than they were disturbed by the old man. Now Eli was allowed into the cellar to hide the books. He couldn’t carry very many at a time—there were days when he felt so weak, so hungry, he could only carry a single volume, and he spent all his breath navigating that long staircase. Eli thought of the cellar library as belonging to him too now, and one night when Josef’s coughing kept him awake, he didn’t hesitate to venture down the steps to sit by the candle-light.

The corridor stretched deep under the earth; it seemed to have grown longer in the weeks since his first visit, expanding to accommodate the ghetto’s rescued volumes. Light washed the books’ spines, tall and squat, brown and black, embroidered with script that flowed from thin to thick, blocky to loopy, Cyrillic to Oriental. He moved on, faster and faster toward the lit alcove, until a strange sound stopped him. Weeping so tormented he thought it was the original language of despair.

Old Solomon sat behind his desk. He lifted his hands to cover face his face, and the sleeves of his robe slid down to his bent elbows.

Eli’s eyes closed against a sudden sharp light. He forced them open again. Uncle, he said.

The old man lowered his hands. His face was covered in shadows, the whole room dim once more. But then he wiped his face with the edge of his sleeve, and the light flared again, forcing Eli to cover his eyes.

The boy was determined to speak to his uncle like a man, unafraid. He lifted the books from the second chair and sat down, holding them in his lap. Are you weeping because of the Germans? he asked.

The Germans? the old man repeated. Why should I weep for them? They are far from us.

His uncle was unconcerned about the severity of what was happening outside his tiny house, and Eli had interpreted his carelessness as senility. Now his mind returned to the lengthening corridor and the infinite shelves, and a story his father once told him about how the White Rebbe left this world. A dream led him to a cave. He sent a goat into its maw and waited three days; when the animal didn’t return, the rebbe knew he had found a magic passage to the Holy Land. He crossed into the darkness and was never seen again.

But of course, this was just an ordinary cellar. His uncle was old and forgetful.

I weep, his uncle continued, for my beloved.

In the time since the brothers had come to Vilna, Eli had learned never to ask anyone where an absent friend, brother, sweetheart might be. No one asked him where his parents were, and he was grateful for that.

But without prompting, his uncle continued. I met her in a city of tides and ships, starlight above us and starlight reflected below. And I cry for my brother, who left on a pilgrimage and never returned. He spread his arms across the table, and the light flashed again.

Uncle, the candle! Eli cried, fearing his sleeve must have caught fire, though eve

n as he uttered the words, he realized that there were no candles. That light, he said. Where is it coming from?

The old man raised his left arm and his sleeve fell, gathering at his shoulder. Blue veins snaked from the ink-stained heel of his palm down his forearm, disappearing into a blaze of light, like rivers into a cataract.

My Sabbath Light, he said, squinting into the wreath of flame. He passed his right hand over the blaze, tamping down the light and revealing that it had a shape, a bright spine that twisted and curled against his skin. Eli tilted his head from side to side, but just when he thought he recognized the shape—a flower, an eye, a snowflake—it slipped into another form.

The old man dropped his arm, and his sleeve fell to his wrist. The light in the room dimmed to twilight. Eli wiped his eyes, which were tearing from the brilliant glare. He stared at his uncle for several long seconds; the afterimage of the Sabbath Light veiled Solomon’s face. A child’s fairy tale had become a young man’s reality. It was not difficult to accept. It was no stranger than his parents’ disappearance or the Vilna Ghetto itself or watching his little brother die of starvation and consumption.

You’re the White Rebbe, Eli said. The wonder-worker. (And now his voice was hushed by awe.) You really did escape death.

Leave me! the White Rebbe raged. Eli turned and ran, while behind him the rebbe’s voice broke into a wave of grief. Oh, why did you come here? the old man wailed. Why did you find me?

THE NEXT DAY THE GHETTO WAS IN CHAOS. THE RUMOR was that Ghetto 2 was to close, and a new crush of people would soon flood the streets of Ghetto 1. But when the new residents finally did arrive, they were very few. The rest had been put on a train. They were gone.

Josef’s teeth began to fall out. The brothers couldn’t remember if they were his remaining baby teeth or new adult teeth, but nothing grew in their place. Eli dreamt that his mother came to their bed beneath the kitchen table and held Josef in her lap, rocking him and stroking his hair, but she wouldn’t look at Eli, she sent him away, and—

I was in darkness.

Eli went to the edge of the ghetto, where the black market flourished, where Christians and Jews passed through the crumbling brick wall as if through a hole in the world, as if through the White Rebbe’s cave connecting Vilna and Jerusalem. He was sure that Josef suffered from living on bread and soup, bones and stray fibers of meat.

If I could find him an egg—a miraculously round egg—it would heal him.

But there were no eggs, not that day. Eli waited by the hole in the wall, sitting with his head in his hands, unwilling to return home and face his starving brother. A procession of Hasids passed by, tattered coats and dirt-painted faces. Penitents, they called themselves. Sometimes people paused respectfully when the band appeared, or momentarily joined their prayer. Other times they ignored them entirely. Eli glared. These self-righteous mourners were spending the last of their energy praying to a useless God. The boy could barely contain his fury at the sight of them.

Night arrived. The first snow of the season began floating down, fine as salt. There was rumbling in the distance—not thunder, Eli thought. The death train. But unlike the train that had emptied Ghetto 2, that had taken its people far away, this one was coming closer. This one was coming for him alone; no matter how many eggs he collected, no matter how clever he proved himself to be, no matter how many miles he ran, one day that train would reach him. When it did, it would be filled with all of the people he loved, and all of the things they knew—the dialects they joked in, the melodies they hummed, the smells of their cooking, the recipes unwritten, the ingredients once harvested from fields now poisoned by blood—all of these things would beckon me, and no matter how I try to forget, no matter the words I refuse to say, the memories I let wither, the blessings I leave unsaid, in the end there will be the train, there will be my death, the very same death, the only death, and I will fall on my knees before it, and my sins will rise up like a school of golden fish, and they will fight one another in my gullet, and I will clutch my throat. The specters behind the train windows will watch tears stream from my eyes and my empty lungs shudder and my limbs lose feeling and my sins choke me; they will watch while my vision fades and the last bit of life buzzes under my skin, they will watch me die, and then they will open their arms and take me.

THE NEXT DAY THERE WERE POSTERS EVERYWHERE—the ghetto would have its first theater performance, sponsored by the Judenrat. The streets were blanketed with flyers: You don’t make theater in a graveyard. The Socialists were rumored to be building bombs, sensing that the time to save ourselves was running low. The remaining Jewish books in Vilna flooded the Jewish library. Rosenberg was coming to make his selection. Everyone knew now.

We knew that the Germans were going to kill us, kill us all.

Eli determined that it was time for him and Josef to flee again. He descended into the cellar one last time. As always, the White Rebbe was at his desk, working in one of his ledgers, his quill whipping the air. I know who you are, Eli said. You can save us.

The rebbe laughed—a sound so chilling that Eli’s frostbitten bones shivered anew. Do you feel that in the air? the rebbe asked. The crackle of imminent lightning? The new wind that has come upon us like a wave, bringing the bitter scent of cinders? The Angel of Losses is here. I must leave.

For years, he said, I have refused to perform wonders. I have lived here quietly, and I have remained hidden. Now I can no longer turn away—but it is too late. My mind has grown twisted. My magic has begun to rot. I am no use to the people here.

Eli thought of the good omens the ghetto had observed. The shooting star had preceded a hailstorm—windows broken, a man hit in the head and killed. The family healed of tuberculosis—dead a week later when fire broke out in their room. The baby born with a star on his skin—a cruel joke, perhaps a death sentence.

But you are supposed to be our hero, Eli said quietly, feeling as if he might weep, the flash of hope followed by the searing defeat nearly too much for him to bear. Nearly.

If I had died, the White Rebbe said, I would have been a hero. But I lived. And in living, the most important pieces of me have died one by one.

If you will not be a hero, Eli declared, I will.

The White Rebbe raised his sleeve, releasing a wave of light. Eli’s eyes burned as if a great gust of wind had assaulted them with grit, but he forced them open. He forced himself to see it through his tears, the vague and shifting shape.

This is the Sabbath Light, the rebbe said. It’s the final letter of the alphabet, the letter that completes creation. It was the Angel of Losses’s greatest treasure and greatest secret, until our ancestor, the first Berukhim Rebbe, compelled him to share it. Now the angel has been punished, cast out of heaven. It is why he wanders like a penitent—he is bereft, he is desperate to return home, beyond the River of Stones, to paradise.

I would give it back to him, if I could, but it belongs to humanity now. It illuminates the passage between this land and the land beyond, between our bodies and our souls. I cannot relinquish it without choosing a successor, and I can’t foist it on an unwilling host.

I will carry it, Eli said. He recognized the Sabbath Light as the source of the White Rebbe’s magic, and magic might be the only thing that could save Josef and himself. Nevertheless, he felt doubt. The White Rebbe of the stories had been noble and holy, and Eli believed himself to be neither.

There is a price. A debt owed to the angel, one that every Berukhim Rebbe has failed to fulfill.

I don’t care.

No, the rebbe said. You will listen.

The old man told his story, the secret history of the White Rebbe and the Angel of Losses. Yet Eli’s mind wandered. Half of him listened and half of him only waited, for he cared little for the rebbe’s warnings.

I had become crafty in my desperation to escape, to survive, prepared at any second to argue for my worth, my life. Concerned only with this moment, and the moment next to come.

E

li agreed to the old man’s terms. He would take the Sabbath Light and its magic, along with the promise his ancestors, every rebbe since the Holy Land, owed the Angel of Losses; and the White Rebbe would finally lay down his centuries and rest.

THE NIGHT OF THE JUDENRAT’S PLAY, THE BROTHERS performed their ritual a second time—dressing in two pairs of pants, two shirts, their father’s prayer shawl wrapped around Josef’s body. He was so skinny by then that it fit easily beneath his other clothes. Don’t worry, Eli told him. The White Rebbe will protect us.

But when he opened the cellar door to bid farewell to his uncle, and to receive the Sabbath Light, there was only blackness. Eli reached into the space, but on all three sides his hands hit walls. He closed the door and opened it again. He thought that in his haste, in his fear, he had become turned around in the small room, but no—it was the only door, and it led nowhere.

JOSEF AND I FLED INTO THE NIGHT. A STAGE HAD BEEN built outdoors, and a huge crowd gathered before it. We walked through the front doors of homes and out the back, bypassing the audience. Everywhere we went, we could hear their swells of laughter, their clapping.

The long years of his unnatural life had worn away the goodness in the White Rebbe; the lost letter had engulfed him with a yearning to cross the River of Stones, where the same light illuminated the land. Or perhaps his fear returned, and he had abandoned us upon sensing the approach of his old enemy, the Angel of Losses.

Our escape was up to me alone.

Fortunately, I had already devised a plan.

But I want to see the play, Josef said, between fits of coughing.

Shut up, I said.

The alley by the ghetto wall was empty. We would have to escape through the hole—I had a pass that would let me walk freely through the front entrance tomorrow morning, but this was Josef’s only exit.

The Angel of Losses

The Angel of Losses